YouTube’s decaying user experience has a more significant role to play in piracy than ad blocking

It’s always the innocent civilian who is the casualty of any war. It would be unfair to say that YouTube’s crusade against third-party apps has quite the gravity of war. However, the fact of the matter is that, once again, it is the customers who are caught in the crossfire of the company’s relentless pursuit to thwart third-party apps. Something’s got to give.

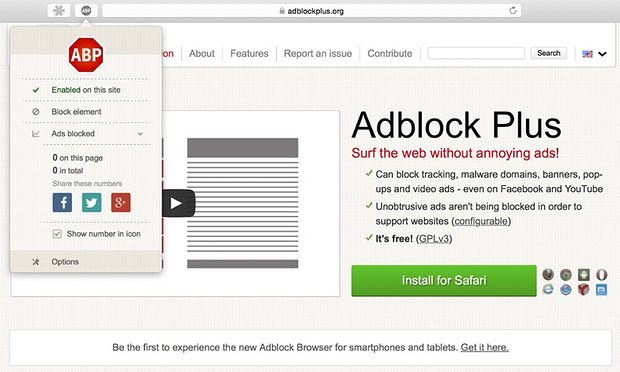

Recently, YouTube stated that it would strengthen its enforcement against apps that help users circumvent ads, circling us right back to YouTube’s other unwinnable war, its war against ad blockers. However, there’s a fallacy in YouTube’s understanding of the issue. Ad-blocking is just one feature offered by third-party YouTube apps and doesn’t necessarily even require another app. These alternative YouTube apps open up a world of quality-of-life additions that YouTube has either decided to remove or wasn’t thoughtful enough to include in the first place. And avid YouTube enthusiasts aren’t about to give up on these incredible features in the face of the company’s threats.

Ad-blocking is just one reason to install a third-party YouTube app

YouTube’s cheapening of the user experience has a larger role to play

Understanding YouTube’s ham-fisted approach against third-party apps requires understanding why people care enough to jump through loopholes to sideload these apps. It would be fairly trivial to point at ads as the singular problem with YouTube. However, that would be trivializing the extent of the issue. Ads have almost always been part and parcel of the YouTube experience. However, there’s a point at which ads become so frequent, so irrelevant, and so relentless that they start hurting the user experience. We’ve been past that point for a while now.

Scour community forums like Reddit, and you’ll spot user complaints about people having to sit through back-to-back ads after watching a single video. The other day, I had to sit through three 30-second long ads, two seemingly unskippable, to watch a minute-long video. That’s ridiculous. YouTube’s sneaky methods of hiding away skip buttons add to the menace.

But that’s not all there is to it. YouTube’s entire user experience has been going downhill for years. Pop open the app, and you’ll be bombarded by utterly unrelated content that has nothing to do with what you’ve been watching. Whatever happened to personalization, YouTube? The issue isn’t recent, either. By all estimates, the tipping point was somewhere around 2016. However, it’s just been getting worse. I don’t see a correlation between stand-up comedy and an account that only follows engineering and history documentaries, but perhaps I’m missing something.

Moreover, those unrelated recommendations have completely taken over my subscriptions. Unless I deep dive into the subscriptions tab, the app won’t show me all the new content that creators I follow have been putting out. There used to be a time when I’d pop into an exciting video and be taken down a rabbit hole of related videos I could binge through the night. That time has gone and has been gone for a while now.

Unfortunately, I wish solid recommendations, or the lack thereof, were the last of my concerns. It’s not, and the mobile app’s degradation has almost put me off watching YouTube on my phone. As I write this piece, my homepage consists of a sponsored ad for a television show in a language I don’t understand. This is followed by a 2 x 4 grid of YouTube Shorts with content unrelated to my subscriptions and watch history. Perhaps there’s a missing connection between Bollywood dance and Czechoslovakia’s Socialist history, but I fail to see it. Stay put because it doesn’t end there. You’ll also find a few more ads and occasionally an entire section dedicated to YouTube Music. Sigh. It really shouldn’t come as a surprise to Google that users are starting to retaliate.

Elsewhere, the app keeps making watching high-quality videos more complicated. My data limit is high enough that I don’t need to micromanage YouTube’s data consumption. If I’ve set it to high-quality playback, I want it to be the case for all the videos I watch. Except, that isn’t the case. Repeatedly, the app swaps out the high-quality stream for a mobile-optimized option.

Third-party apps offer a better YouTube experience than YouTube itself

Sometimes, Less is more

Based on the company’s statements, it’s clear that Google thinks third-party apps exist to remove ads. Sure, that might be the case for a significant number of users. However, these apps also add quality of life additions — A concept that is alien to the company. Dislikes? Who needs them? Right?

Third-party apps let users take control of their feeds. Apps like Revanced let you remove shorts from your home feed, get rid of obtrusive end screen cards, or do things like repeat a particular video — a must-have if you have a go-to focus music track.

Elsewhere, tools like SponsorBlock are a godsend for scrubbing past annoying sponsored segments within a video. This is not content that Google can monetize and should have no issue with. I won’t go into the ethics of supporting a creator you like. My gripes tend to be with creators who agree to partner with unscrupulous companies for a quick buck. But that’s a debate for another day.

YouTube vs. Third-party apps: A cat and mouse game

Third-party apps aren’t going anywhere

I have little hope that the collective protests of YouTube enthusiasts will change the company’s stance. As video consumption grows multifold year-on-year, Google has a business to run, and ads are its business, not entertainment. It wants you to watch more videos, any videos. Pushing clickbait and conspiracy theories is bound to pique the curiosity of most of us. Similarly, the push to bring podcasts to YouTube is driven by the desire for a consolidated user base to monetize through ads. And it’ll do everything it can to boost engagement over usability. Any additional tap, accidental even, is worth it. It’s pure speculation on my end, but I think it would be fair to say that YouTube’s UX focuses on making the experience annoying enough that users will eventually be compelled to pay for YouTube Premium.

But here’s where YouTube is mistaken — third-party apps aren’t going anywhere. Developers erring on the rebellious side of the internet tend to have a dog-headed approach. The recent example of Nintendo striking down emulators shows that, like the proverbial Hydra, if you chop off one head, another head, or in this case, fork, is bound to pop up. The more Google pushes back, the more developers are bound to double down on their efforts. It might take longer for devs to circumvent some restrictions, but I don’t see any scenario where third-party YouTube apps won’t exist.

YouTube’s monopoly on video streaming guarantees that we haven’t seen the last of this cat-and-mouse game. Google’s “Don’t be evil” days might be behind it, but it would do well to take a step back on pursuing alternative app developers and focus more on improving its core user experience. It only makes it look more evil.

By Dhruv Bhutani

Dhruv Bhutani has been writing about consumer technology since 2008. He brings extensive insights into the Android smartphone landscape, which he translates into features and opinion pieces.