By Ben Thompson

If the first stage of competition in consumer technology was the race to be the computer users went to (won by Microsoft and the PC), and the second was to be the computer users carried with them (won by Apple in terms of profits, and Google in terms of marketshare), the outlines of the current battle came sharply into focus over the last month: what company will win the race to be the computer within which users live?

The Announcements

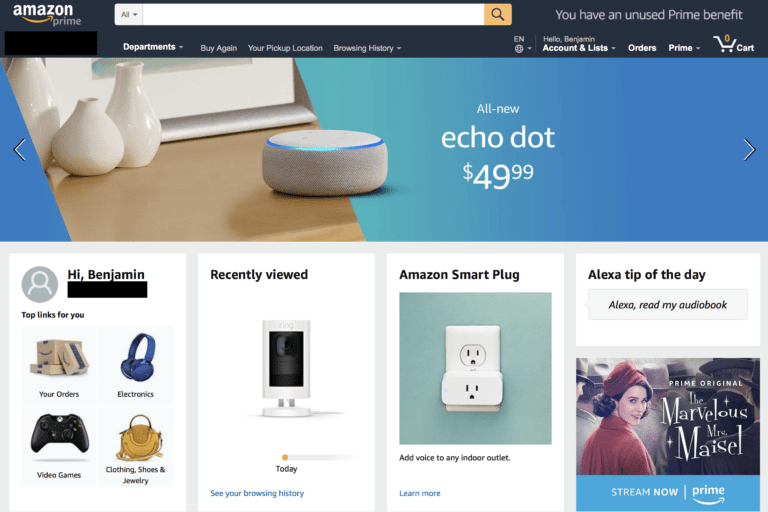

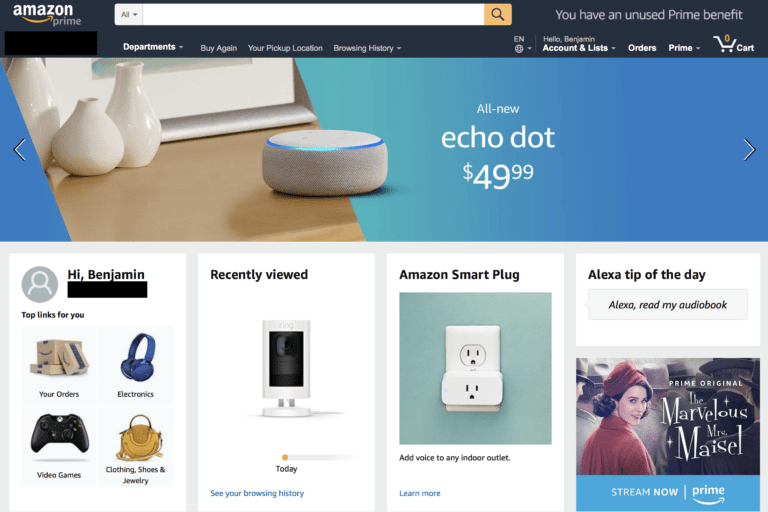

The first announcement came from Amazon three weeks ago: a new high-end Echo Plus, Echo Dots, several Echo devices for use with 3rd party stereos and speakers (or other Echoes), and an updated Echo Show (i.e. an Echo with a screen). All standard fare, and then things got wacky: the company also announced a microwave, a wall clock, smart plugs, a device for the car, and a TV Tuner/DVR, all with Alexa built-in.

Next up was Facebook: earlier this week the company launched the Portal, a video chat device that can track faces, has Alexa integration, and a smattering of 3rd-party apps likes Spotify. The device was reportedly delayed last spring as the company grappled with the fallout of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and was instead launched in the midst of a data exposure scandal.

Third was Google: yesterday the company announced the Google Home Hub — a Google Home with a screen attached, a la the Echo Show — as well as the Pixel 3 phone and the Pixel Slate tablet, along with far deeper integration between Nest home automation products and the Google Home ecosystem.

And, of course, there is Apple, which launched the HomePod earlier this year, and added a few new capabilities with a software update last month.

Each of these companies brings different strengths, weaknesses, go-to-market strategies, and business models to the fight for the home; a question that is just as important of who will win, though, is to what degree it matters.

Strengths

Each of these companies’ strengths in the home is closely connected to their success elsewhere.

Amazon: Amazon deserves to go first, in large part because they were first: while Google acquired Nest in 2014, Nest itself was predicated on the smartphone being the center of the connected home. Amazon, though, thanks to its phone failure, had the freedom to imagine what a connected home might look like as its own independent entity, leading the company to launch the Echo speaker and Alexa assistant in late 2014.

I was immediately optimistic, in part because the Echo was everything the failed Fire phone was not: its success depended not on the integration of hardware and software, the refinement of which a service company like Amazon is fundamentally unsuited for, but rather the integration of hardware and service. It also helped that Amazon had a business model that made sense: on one hand, the investments in Alexa would pay off with services for AWS, and on the other, Amazon’s goal of taking a slice of all economic activity was by definition centered around capturing an ever-increasing share of purchases made for and consumed in the home, and Alexa could make that easier.

That led to an early lead in the development of the Alexa ecosystem, both in terms of “Skills” and also in devices that incorporated Alexa. As I noted in 2016, this made Alexa Amazon’s operating system for the home, and today Alexa has over 30,000 skills and is built into 20,000 devices.

That, though, makes Amazon’s recent announcements that much more interesting: Amazon isn’t simply content with being the voice assistant for 3rd-party devices, it also is making those devices directly. This, by extension, perhaps points to Amazon’s biggest strength: because Amazon.com is so dominant, the company can have its cake and eat it too. That is, just as Amazon.com is both a marketplace and a channel for Amazon to sell its own products, Alexa is both a necessary component of 3rd-party devices and also a driver of Amazon’s own devices; the company faces no strategy taxes in its drive to win.

Google: Google was very late to respond to Alexa; the original Google Home wasn’t announced until May 2016, and didn’t ship until November 2016, a full two years after the Echo. The company was, as I noted above — and as you would expect for a market leader — locked into the smartphone paradigm; an app plus Nest was its answer, until Alexa made it clear this was wrong.

Google, though, has started to catch up, and the reason is obvious: if a home device is about the integration of hardware and services, it follows that the company that is best at services — consumer services, anyways — would be very well-placed to succeed. The company still trails Alexa by a lot in actions/skills (around 2,000) and 3rd-party devices (over 5,000), but Google’s core functionality is plenty strong enough to sell devices on its own. There are still more Echoes being sold, but Google Home is catching up.

To that end, one of the more interesting takeaways from yesterday’s Google event was the extent to which Google is leaning on its own services to sell its devices: not only did the company tout the helpfulness of Google Assistant, it also prominently featured YouTube, particularly in the context of the Google Home Hub. This is particularly noteworthy because Google handicapped the YouTube functionality of the Echo Show, clearly with this product in mind. Google is also including six months of YouTube Premium with a Google Home Hub; indeed, every Google product included some sort of YouTube subscription product.

Apple: The HomePod is exactly what you would expect from Apple: the best hardware at the highest price. The sound is excellent and, naturally, even better if you buy two. The HomePod is also — again, as you would expect from Apple — locked into the Apple ecosystem; this is from one perspective a weakness, but this is the Strength section, and the reality is that people are more committed to their iPhones — and thus Apple’s ecosystem — than they are to home speakers, meaning that for many customers this limitation is a strength.

Along those lines, Apple is clearly the most attractive option from a privacy perspective: the company doesn’t sell ads, has made privacy a public priority, and is thus the only choice for those nervous about having an Internet-connected microphone in their house.

Facebook: Perhaps the most compelling case for Portal is historical. In the introduction I framed the battle for the home as following the battle for the desk and the battle for the pocket. There were, though, intervening battles that were enabled by those fights for physical spaces. Specifically, the PC created the conditions for the Internet, which in turn made smartphones that could access the Internet so compelling. Smartphones, then, created the conditions for social networking (including messaging) to infiltrate all aspects of life.

Might it be the case, then, that just as the Internet was the key to unlocking the potential of mobile, so might social networking be the key to unlocking the potential of the home? That appears to be Facebook’s bet: sure, the device has some neat hardware features, particularly the ability to follow you around the room or zoom out during a call, but neat hardware features can and will be copied. If Portal is to be a successful venture for Facebook, it will be because the tie-in to Facebook’s social network makes this device compelling.

Weaknesses

As is so often the case, each companies’ weakness is the inverse of their strength:

Amazon: Amazon simply isn’t that good at making consumer products. In my experience its devices are worse than the competition both aesthetically and in terms of hardware capabilities like sound quality. In addition, Amazon’s brute force skills approach — it is on the user to speak correctly, not on the service to figure it out — lends itself to more skills initially but a potentially more frustrating user experience.

Amazon also has less of a view into an individual user’s life; sure, it knows what kind of toothpaste you prefer, but it doesn’t know when your first meeting is, or what appointments you have. That is the province of Google in particular, and also Apple. What is more valuable: being able to buy things by voice, or being told that you best be leaving for that early meeting STAT?

Google: As a product Google’s offering is remarkably strong (there are other weaknesses, which I will get into below). The company is the best at the core functionality of a home device, and it knows enough about you to genuinely add usefulness. Its products are also more attractive and better-performing than Amazon’s (in my estimation).

Google does face questions about privacy: the company collects data obsessively — right up to the creepy line, as former CEO Eric Schmidt has said — and that could be a hindrance to the company’s ability to penetrate the home. That said, Google has so far escaped Facebook-level scrutiny, and wisely excluded a camera from the Google Home Hub. Google knows its advantage is in providing information; it has sufficient other avenues to collect it, without putting a camera in your bedroom.

Apple: Apple, even more than Google, seemed blinded by its smartphone success. This isn’t a surprise: the ultimate point of Android was to be a conduit to Google’s services; it follows, then, that if home devices are about services, that Google would be more attuned to the opportunity (and the threat). Apple, on the other hand, is and always will be a product company; the company offers services to help sell its hardware, not the other way around, and it follows that the company would be heavily incentivized to insist that the iPhone and Apple Watch, which both offered attractive hardware margins and were differentiated by the integration of hardware and software, were better home devices.

That, furthermore, explains Apple’s biggest weakness: the relative performance of Siri as compared to Alexa or Google Assistant. The problem isn’t a matter of trivia, but rather speed and reliability. Siri is consistently slower and more likely to make mistakes in transcription than either Alexa or Google Assistant (and, for the record, more likely to fail trivia questions as well). As always, Apple is the most potent example of how strengths equal weaknesses: just as it was inevitable that a services company like Amazon would be poor at product, a truly extraordinary product company like Apple will face fundamental challenges in services.

Facebook: If the strengths of Facebook Portal were largely theoretical, the weaknesses are extremely real: it is, frankly, mind-boggling that the company would launch Portal given the current public mood around the company. And, to be clear, that mood is largely deserved; I wrote last week about the company as a Data Factory, and one of the telling examples was how Facebook lets advertisers use numbers provided for two-factor authentication for targeting. This strongly suggests that, from Facebook’s perspective, data is data: everything is an input, and while the company may promise that Portal is private, one wonders why anyone would believe them.

That notes, I actually suspect Portal data is private; this seems like more of an attempt to enhance the value of the Facebook graph, and thus the app’s stickiness, than to collect more data. The problem, though, is that Facebook is not in the position to expect nuance, and that this product was launched anyways supports the argument that the company’s executives are indeed out of touch.

Go-to-Market

The various go-to-market possibilities for these four companies could very well have been folded into strengths-and-weaknesses, but it’s worth highlighting on its own, given how important an effective go-to-market strategy is in consumer products.

Amazon: This is arguably Amazon’s biggest strength: not only does the company have direct access to the top e-commerce site in the world and one of the largest retailers period — and, because it is them, can skip a retailer mark-up — it also gets access to prime real estate:

There is not only no question in a consumer’s mind about where to buy an Echo, it is also nearly impossible that they not know about it. Moreover, Amazon has a second trick up its sleeve: it doesn’t stock any of its competitors products, making acquiring them that much more of a hassle.

Google: I highlighted this as a major Google weakness when it launched its #MadeByGoogle line two years ago, but to the company’s credit, it has worked hard to build out its channel. Today Google products are available on most non-Amazon e-commerce sites and in retailers like Best Buy, Target, and Walmart. The company has also invested in advertising to build awareness; there is still a long ways to go, to be sure, and go-to-market remains a Google weakness, but the company has impressed me with its work in this area.

Apple: This is a huge area of strength of Apple as well. The company obviously has a very strong channel, both online and through its retail stores. Both reflect Apple’s biggest strength, which is its brand: there is no company that has more loyal customers, and those customers are tremendously biased to buy an Apple product over a competitors; they are also more likely to be receptive to Apple’s privacy message, perhaps because they care, or perhaps because that is the message that plays to Apple’s strengths.

Facebook: It appears the company learned nothing from the Facebook First flop. The Facebook First, if you don’t recall, was Facebook’s ill-fated phone; it was manufactured by HTC and was discontinued within weeks of launch. There simply was no evidence that customers wanted to pay for a product that was predicated on Facebook integration, and there was certainly no effective go-to-market strategy.

It is hard to see how the Portal will be different: again, the defining feature is that the camera follows you around, a feature that is cool in theory but bizarrely out-of-touch with Facebook’s current perception in the market. Is the company really going to spend the millions necessary to market this thing? And if so, where is it going to be available to purchase? I can see why this product was designed; I see little understanding of how it might be sold.

Business Models

This too ties into strengths-and-weaknesses, but like the go-to-market strategies, is worth calling out in its own right:

Amazon: I explained the company’s business model above: Amazon wants to own the home, because it sells a huge number of items that are used in the home. This is why the company is willing to press its advantage as both a platform and retailer when it comes to Alexa devices: winning has a very direct connection to the company’s ultimate upside.

Google: The business model is a bit fuzzier here: Google makes money through ads sold in an auction where the winner is chosen by the user. That is a model that doesn’t work for voice in particular; affiliate fees are less profitable given that they foreclose the possibility of an advertiser forming a direct relationship with the end user. That noted, the introduction of a visual interface does also offer the possibility of ads.

More noteworthy is the incorporation of YouTube: YouTube has seen the addition of more and more subscription services, including YouTube Premium, YouTube TV, and YouTube Music. All of these work in conjunction with Google’s designs on to the home.

The most compelling business case for Google, though, is the same as it ever was: maintaining a dominant presence in all aspects of a user’s life, not just on the go (in the case of Android) but also in the home provides the data for more effective advertising in the places where it makes sense. No, Google may not sell that many voice ads, but voice interaction will affect what ads are shown in Search, and that is worth an awful lot.

Apple: Apple’s business model is the most straightforward: HomePod is clearly sold at a profit, part of Apple’s strategy of increasing its monetization of its current userbase. This is also a limitation: as noted above, the HomePod is significantly more expensive than any of its competitors.

Facebook: The social network company has the weakest business model story of all: there are no add-on services to sell, and the company has promised not to use the Portal for advertising, for now anyways. The best argument is similar to Google: more data and more engagement means more opportunities to show better-targeted ads on the company’s other products.

Winners and Losers

There are compelling cases to be made for at least three of the four companies:

Amazon: Amazon’s head start is meaningful, and its widespread integration with other products mean it is likely that more people have a device with Alexa integration than not. The company is also highly motivated to win and has the business model to justify it.

Google: I find Google’s case the most compelling. Product is not the only thing that matters, but it is awfully important, and Google is the best placed to deliver the best product. Its services are superior, its knowledge of users the most comprehensive, and its overall product chops have improved considerably. Yes, its go-to-market is worse than Amazon’s and it has a late start, it is still early.

Apple: The loyalty of Apple’s userbase cannot be overstated, particularly when you remember that the company’s userbase are the most affluent customers of all. This makes it difficult to ever count Apple out, even if their product is late and tied to the worst services.

Facebook: It is hard to envision how Portal won’t be a loser: the company has no natural userbase, has a terrible reputation for privacy, and has no obvious business model or go-to-market strategy.

Does It Matter?

There is one final question that overshadows all-of-this: while the home may be the current battleground in consumer technology, is it actually a distinct product area — a new epoch if you will? When it came to mobile, it didn’t matter who had won in PCs; Microsoft ended up being an also-ran.

The fortunes of Apple, in particular, depend on whether or not this is the case. If it is a truly new paradigm, then it is hard to see Apple succeeding. It has a very nice speaker, but everything else about its product is worse. On the other hand, the HomePod’s close connection to the iPhone and Apple’s overall ecosystem may be its saving grace: perhaps the smartphone is still what matters.

More broadly, it may be the case that we are entering an era where there are new battles, the scale of which are closer to skirmishes than all-out wars a la smartphones. What made the smartphone more important than the PC was the fact they were with you all the time. Sure, we spend a lot of time at home, but we also spend time outside (AR?), entertaining ourselves (TV and VR), or on the go (self-driving cars); the one constant is the smartphone, and we may never see anything the scale of the smartphone wars again.