By

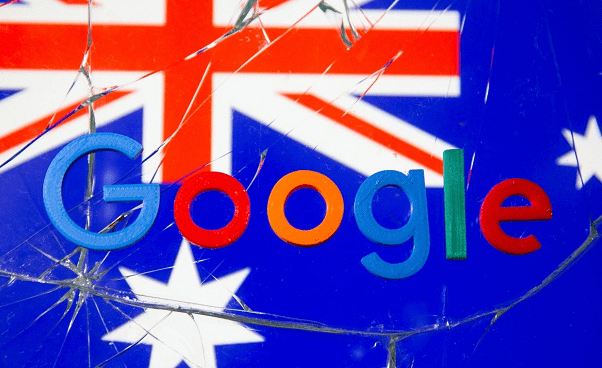

Are Google and Facebook really prepared to pull services from their Australian users rather than hand over some money to publishers under the bargaining code?

Executives from Google and Facebook have told a Senate committee they are prepared to take drastic action if Australia’s news media bargaining code, which would force the internet giants to pay news publishers for linking to their sites, comes into force.

Google would have “no real choice” but to cut Australian users off entirely from its flagship search engine, the company’s Australian managing director Mel Silva told the committee. Facebook representatives in turn said they would remove links to news articles from the newsfeed of Australian users if the code came into effect as it currently stands.

In response, the Australian government shows no sign of backing down, with Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg both saying they won’t respond to threats.

So what’s going on here? Are Google and Facebook really prepared to pull services from their Australian users rather than hand over some money to publishers under the bargaining code?

Facebook claims news is of little real value to its business. It doesn’t make money from news directly, and claims that for an average Australian user less than 5% of their newsfeed is made up of links to Australian news.

But this is hard to square with other information. In 2020, the University of Canberra’s Digital News Report found some 52% of Australians get news via social media, and the number is growing. Facebook also boasts of its investments in news via deals with publishers and new products such as Facebook News.

Google likewise says it makes little money from news, while at the same time investing heavily in news products like News Showcase.

So while links to news may not be direct advertising money-spinners for Facebook or Google, both see the presence of news as an important aspect of audience engagement with their products.

On their own terms

While both companies are prepared to give some money to news publishers, they want to make deals on their own terms. But Google and Facebook are two of the largest and most profitable companies in history – and each holds far more bargaining power than any news publisher. The news media bargaining code sets out to undo this imbalance.

What’s more, Google and Facebook don’t appear to want to accept the unique social role of news, and public interest journalism in particular. Nor do they recognise they might be involved somehow in the decline of the news business over the past decade or two, instead pointing the finger at impersonal shifts in advertising technology.

The media bargaining code being introduced is far too systematic for them to want to accept it. They would rather pick and choose commercial agreements with “genuine commercial consideration”, and not be bound by a one-size-fits-all set of arbitration rules.

Google and Facebook dominate web search and social media, respectively, in ways that echo the great US monopolies of the past: rail in the 19th century, then oil and later telecommunications in the 20th. All these industries became fundamental forms of capitalist infrastructure for economic and social development. And all these monopolies required legislation to break them up in the public interest.

It’s unsurprising that the giant ad-tech media platforms don’t want to follow the rules, but they must acknowledge that their great wealth and power come with a moral responsibility to society. Making them face up to that responsibility will require government intervention.

Online pioneers Vint Cerf (now VP and Chief Internet Evangelist at Google) and Tim Berners-Lee (“inventor of the World Wide Web”) have also made submissions to the Senate committee advocating on behalf of the corporations. They made high-minded claims that the code will break the “free and open” internet.

But today’s internet is hardly free and open: for most users “the internet” is huge corporate platforms like Google and Facebook. And those corporations don’t want Australian senators interfering with their business model.

Independent senator Rex Patrick hit the nail on the head when he asked why Google wouldn’t admit the fundamental issue was about revenue, rather than technical detail or questions of principle.

How seriously should we take threats to leave the Australian market?

Google and Facebook are prepared to go along with the Senate committee’s processes, so long as they can modify the arrangement. The don’t want to be seen as uncooperative.

The threat to leave (or as Facebook’s Simon Milner put it, the “explanation” of why they would be forced to do so) is their worst-case scenario. It seems likely they would risk losing significant numbers of users if they did so, or at least having them much less engaged – and hence producing less advertising revenue.

Google has already run small-scale experiments to test removing Australian news from search. This may be a demonstration that the threat to withdraw from Australia is serious, or at least, serious brinkmanship.

People know news is important, that it shapes their interactions with the world – and provides meaning and helps them navigate their lives. So who would Australians blame if Google and Facebook really do follow through? The government or the friendly tech giants they see every day? That’s harder to know.

For transparency, please note The Conversation has also made a submission to the Senate inquiry regarding the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code.

By

Tim Dwyer, Associate Professor, Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney