The tech giant has many ways of gathering information about its users’ activity – from Prime to Alexa. But how much can it collect and what can you do to keep your life private?

rom selling books out of Jeff Bezos’s garage to a global conglomerate with a yearly revenue topping $400bn (£290bn), much of the monstrous growth of Amazon has been fuelled by its customers’ data. Continuous analysis of customer data determines, among other things, prices, suggested purchases and what profitable own-label products Amazon chooses to produce. The 200 million users who are Amazon Prime members are not only the corporation’s most valuable customers but also their richest source of user data. The more Amazon and services you use – whether it’s the shopping app, the Kindle e-reader, the Ring doorbell, Echo smart speaker or the Prime streaming service – the more their algorithms can infer what kind of person you are and what you are most likely to buy next. The firm’s software is so accomplished at prediction that third parties can hire its algorithms as a service called Amazon Forecast.

Not everyone is happy about this level of surveillance. Those who have requested their data from Amazon are astonished by the vast amounts of information they are sent, including audio files from each time they speak to the company’s voice assistant, Alexa.

Like its data-grabbing counterparts Google and Facebook, Amazon’s practices have come under the scrutiny of regulators. Last year, Amazon was hit with a $886.6m (£636m) fine for processing personal data in violation of EU data protection rules, which it is appealing against. And a recent Wired investigation showed concerning privacy and security failings at the tech giant.

So, what data does Amazon collect and share and what can you do to stop it?

The data Amazon collects, according to its privacy policy

Strict EU regulation in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and UK equivalent the Data Protection Act limit the ways personal data can be used in Europe compared with the US. But, according to Amazon’s privacy policy, the tech giant still collects a large amount of information. This covers three areas: information you give Amazon, data it collects automatically and information from other sources such as delivery data from carriers.

Amazon can collect your name, address, searches and recordings when you speak to the Alexa voice assistant. It knows your orders, content you watch on Prime, your contacts if you upload them and communications with it via email. Meanwhile, when you use its website, cookie trackers are used to “enhance your shopping experience” and improve its services, Amazon says.

Some of the data is used for “personalisation” – big tech speak for using your data to improve your online experience – but it can reveal a lot about you. For example, if you just use its online retail site via the app or website, Amazon will collect data such as purchase dates and payment and delivery information.

“From this information, Amazon can work out where you work, where you live, how you spend your leisure time and who your family and friends are,” says Rowenna Fielding, director of data protection consultancy Miss IG Geek.

At the same time, Prime Video and Fire TV information about what you watch and listen to can reveal your politics, religion, culture and economic status, says Fielding. If you use Amazon to store your photos, a facial recognition feature is enabled by default, she says. “Amazon promises not to share facial recognition data with third parties. But it makes no such commitment about other types of photo data, such as geolocation tags, device information or attributes of people and objects featured in images.”

Amazon Photos does not sell customer information and data to third parties or use content for ad targeting, an Amazon spokesperson says, insisting the feature is for ease of use. You also have the option to turn the feature off in the Amazon Photos app or on the website.

Meanwhile, Amazon’s Kindle e-reader will collect data such as what you read, when, how fast you read, what you’ve highlighted and book genres. “This could reveal a lot about your thoughts, feelings, preferences and beliefs,” says Fielding, pointing out that how often you look up words might indicate how literate you are in a certain language.

Smart speakers have been criticised by privacy advocates and devices such as Amazon’s Echo have been known to be activated accidentally. But Amazon says its Echo devices are designed to record “as little audio as possible”.

No audio is stored or sent to the cloud unless the device detects the wake word and the audio stream is closed immediately after a request has ended, an Amazon spokesperson says.

More broadly, Amazon says much of the information it collects is needed to keep its products working properly. An Amazon spokesperson says the company is “thoughtful about the information we collect”.

But it can add up to a lot of data. In 2020, a BBC investigation showed how every motion detected by its Ring doorbells and each interaction with the app is stored, including the model of phone or tablet and mobile network used. Ring can share your stored data with law enforcement, if you give your consent or if a warrant is issued.

How Amazon shares data across its own services

The more services you use, the bigger Amazon’s opportunity to collect your data. “If you have bought fully into the Amazon experience, you will share details, habits and information that the company will collect and potentially use to ‘enhance your experience’,” says Richard Hale, a senior lecturer in digital forensics at Birmingham City University.

But what exactly is shared within its own companies isn’t clear. The privacy policy section on data sharing within the Amazon group of companies is “pretty limited”, says Will Richmond-Coggan, an information and privacy law specialist at Freeths LLP. Taking this into account, he says, people should “assume that any information shared with one Amazon entity will be known to any other”.

How Amazon shares your data with third parties

Like Google and Facebook, Amazon operates an advertising network allowing advertisers to use its customer data for targeting.

“Although Amazon doesn’t share information that can directly identify someone, such as a name or email address, it does allow advertisers to target by demographic, location, interests and previous purchases,” says Paul Bischoff, privacy advocate at Comparitech.

Amazon lets other companies track users visiting its website, says Wolfie Christl, a researcher who investigates the data industry. “It lets companies such as Google and Facebook ‘tag’ people and synchronise identifiers that refer to them. These companies can then potentially better track people on the web and exchange data on them.”

Amazon says it doesn’t sell your data to third parties or use personally identifiable information such as your name or email for advertising purposes. Advertising audiences are only available within its ads systems and cannot be exported and you can opt out of ad targeting via its advertising preferences page.

What you can do to stop Amazon collecting data

Amazon’s data collection is so vast that the only way to stop it completely is not to use the service at all. That requires a lot of dedication but there are some ways to reduce the amount of data collected and shared.

If you are concerned about what Amazon knows about you, you can ask the company for a copy of your data by applying under a “data subject access request”. The Alexa assistant and Ring doorbell have their own privacy hubs that allow you to delete recordings and adjust privacy settings. Ring’s Control Centre allows you to tweak settings including who’s able to see and access your videos and personal information from a central dashboard. Speaking to Alexa, you can say: “Alexa, delete what I just said” or: “Alexa, delete everything I said today.”

Amazon says it allows customers to view their browsing and purchase history from “Your Account” and manage which items can be used for product recommendations. More broadly, you can also use privacy-focused browsers such as DuckDuckGo or Brave to stop Amazon from tracking you.

But it’s not always easy to change the settings on Amazon itself, says Chris Boyd, lead analyst at security company Malwarebytes. He recommends turning off browsing history on Amazon and opting out of interest-based ads to reduce the level of tracking by the company. Yet he warns: “You’ll likely still see ads from Amazon or encounter third-party advertisers in one form or another – they just won’t be as targeted.”

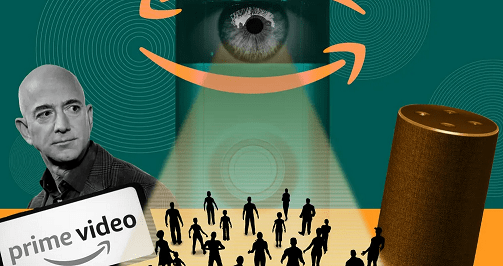

Feature Image Credit: Under scrutiny: Jeff Bezos and his empire of platforms and devices. Illustration: Philip Lay/The Observer