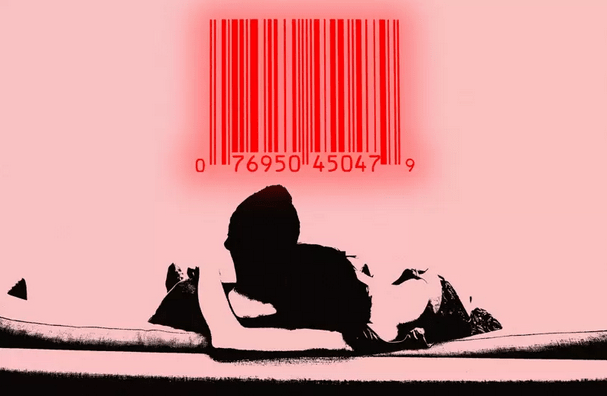

Imagine waking up one day to find that every click, search, and purchase you’ve made online has been carefully catalogued, not just by corporations but by anyone with the means to access it. It’s not paranoia; it’s reality. In a world where your digital footprint is currency, being untraceable is no longer just a preference, it’s a necessity for those who value their privacy. Whether you’re concerned about data breaches, targeted ads that seem to read your mind, or simply the idea of being constantly monitored, the ability to disappear online is a skill that feels more urgent than ever. But how do you take back control in a system designed to track your every move?

This guide, created by Proton, offers a step-by-step guide to reclaiming your privacy and reducing your online traceability. You’ll learn how to limit corporate surveillance, minimize tracking from smart devices, and even compartmentalize your digital identity to shield yourself from prying eyes. For those seeking the ultimate escape, it explores the possibility of complete anonymity, though not without its sacrifices. Each method is designed to empower you, balancing practicality with the level of privacy you desire. Whether you’re looking to protect sensitive information or vanish entirely, this guide will challenge you to rethink how you navigate the digital world. After all, in an age of constant surveillance, how much of your life do you truly own?

Reduce Your Digital Footprint

Key Takeaways :

- Use ad blockers, privacy-focused browsers, and extensions like Privacy Badger to limit corporate surveillance and enhance online privacy.

- Minimize smart device tracking by disabling Wi-Fi and Bluetooth when not in use and consider advanced tools like Pi-hole for network-level protection.

- Compartmentalize your digital identity by using separate email accounts, phone numbers, and payment methods for different activities, supported by password managers for organization.

- Protect personal information in public records by using legal entities, decoy addresses, and regular audits to reduce exposure to unwanted scrutiny.

- Pursue complete anonymity by avoiding traceable devices, using cash or privacy-focused cryptocurrencies, and adopting a non-digital lifestyle if necessary.

1: Limit Corporate Surveillance

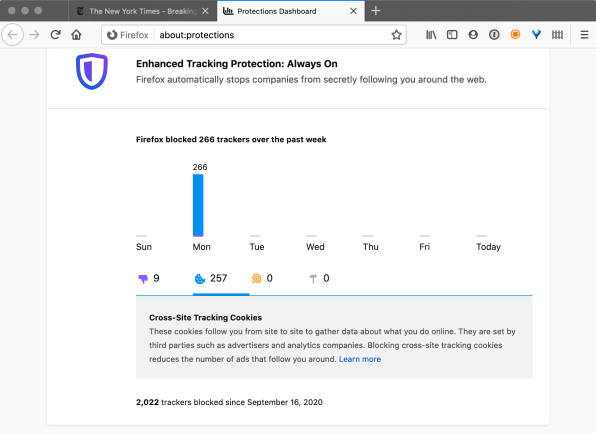

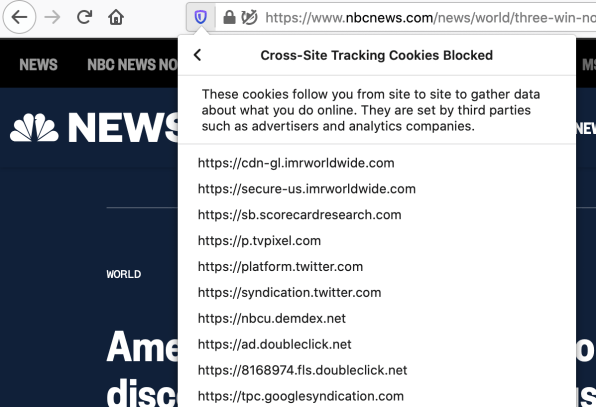

Corporations rely heavily on tracking your online behaviour to create detailed profiles for advertising, pricing strategies, and other purposes. To counter this, begin by using ad blockers. These tools prevent intrusive ads and tracking scripts from monitoring your activity across websites. While effective, some websites may restrict access or functionality if they detect an ad blocker in use.

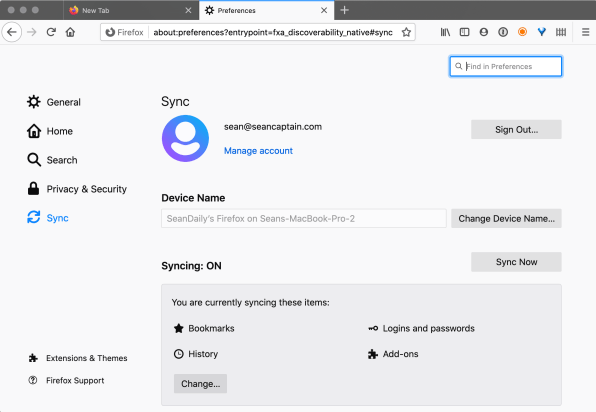

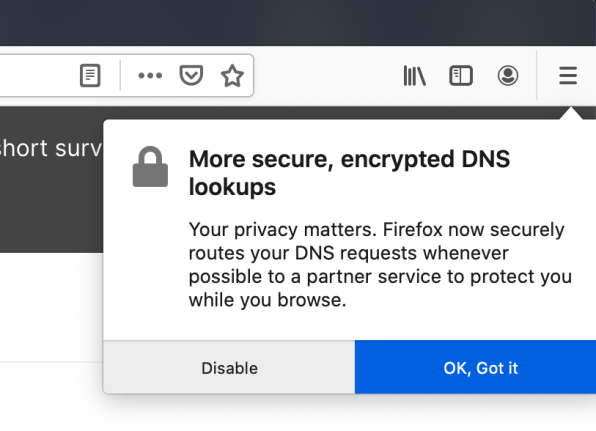

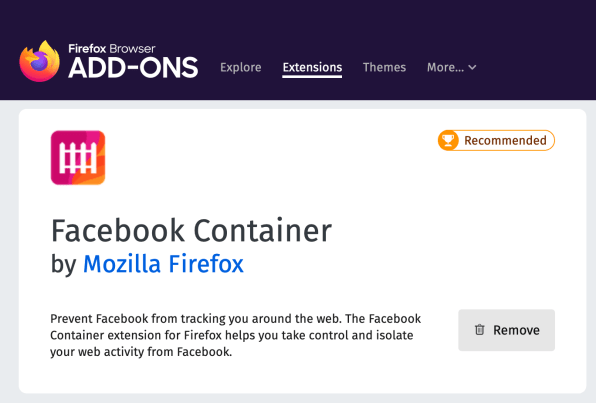

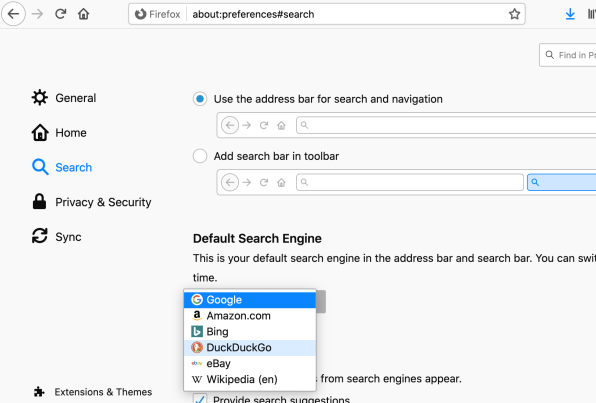

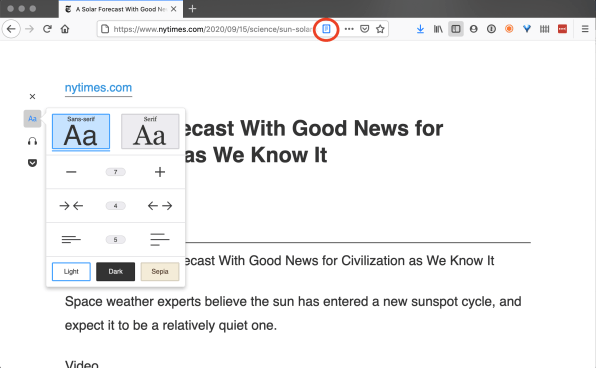

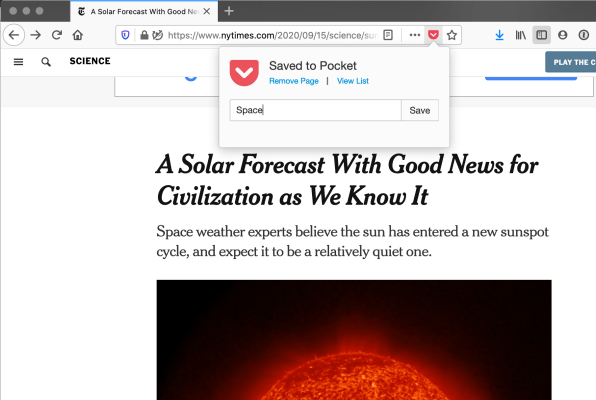

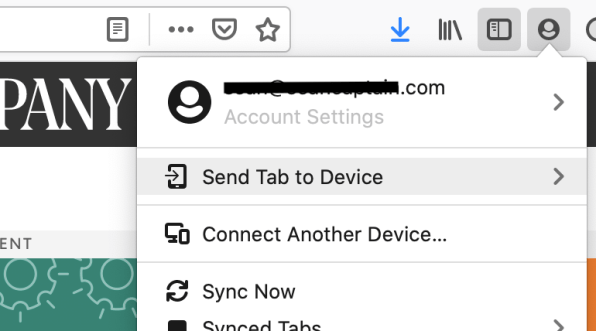

For enhanced protection, switch to privacy-focused browsers like Brave or Firefox, which block third-party cookies and prevent browser fingerprinting. Additionally, consider installing extensions such as Privacy Badger or uBlock Origin to further reduce tracking. These measures may require slight adjustments to your browsing habits, as certain websites might not function optimally. However, the trade-off is a significantly more private online experience, allowing you to browse with greater peace of mind.

2: Minimize Smart Device Tracking

Smart devices, including smartphones, smart speakers, and connected appliances, are designed to collect and transmit data. To reduce this, start by disabling Wi-Fi and Bluetooth when they are not in use. This simple yet effective step prevents your devices from passively sharing information with nearby networks or devices.

For more advanced protection, consider implementing tools like Pi-hole, which blocks unwanted data transmission at the network level. While highly effective, setting up and maintaining such tools can be technically demanding. Additionally, disabling certain tracking features on smart devices may limit their functionality. Evaluate whether these trade-offs align with your privacy priorities, and adjust your approach accordingly.

How to Disappear Online & Become Untraceable

Check out more relevant guides from our extensive collection on digital privacy that you might find useful.

- 7 Essential Encrypted Services to Safeguard Your Privacy & Digital

- MacOS Privacy Reimagined With Emerging VPN Features in 2025

- How to stop your iPhone tracking you in iOS 17 (Video)

- How To Make Your Apple Mac Private : Simple Steps to Protect Your

- Privacy Advocate Exposes All The Ways You’re Being Surveilled

- Best European Alternatives vs US Digital Products : Challenging US

- DIY Raspberry Pi Router for Enhanced Internet Security & Privacy

- How to delete your Google search history

- Western Digital Thunderbolt 3 DAS G-Technology G-Speed Shuttle

- 8 Must-Have Android Apps for November 2024

3: Compartmentalize Your Digital Identity

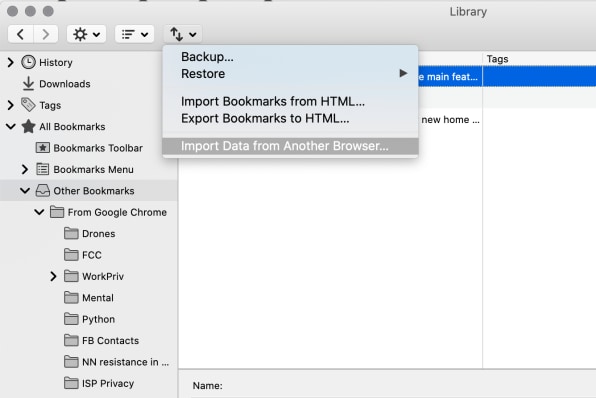

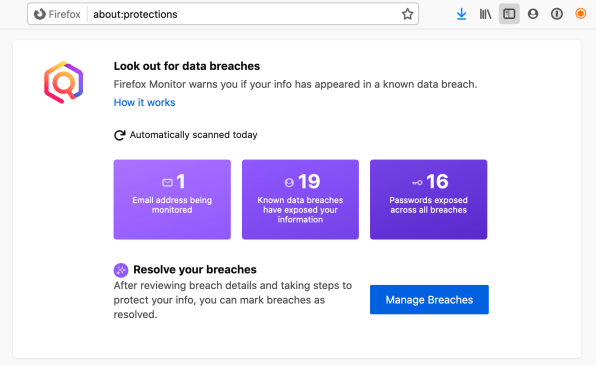

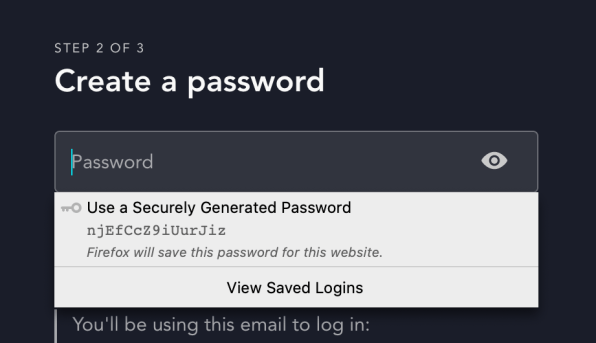

Separating your digital identity into distinct compartments can significantly enhance your privacy. This involves using different email accounts, phone numbers, and payment methods for various aspects of your life, such as work, personal activities, and online shopping. By compartmentalizing your digital presence, you reduce the risk of a single data breach exposing all your information.

While this strategy is effective, it requires careful organization and discipline. Managing multiple accounts and credentials can be time-consuming, but the added security is invaluable for those committed to protecting their privacy. Tools like password managers can simplify this process by securely storing and organizing your login information, making sure that your digital compartments remain distinct and manageable.

4: Remove Public Records and Paper Trails

Public records, such as property ownership and voter registration, can reveal sensitive information like your home address. To obscure these details, consider using legal entities, such as trusts or corporations, to hold assets or manage financial accounts. This approach helps shield your personal information from public view.

Another effective strategy is to establish a decoy address for official purposes, such as a P.O. box or a mail forwarding service. This can help mask your actual location while still allowing you to receive important correspondence. Regularly auditing your privacy measures is also essential. Hiring professionals to identify vulnerabilities in your setup can help you address weaknesses before they are exploited. While these steps require time and effort, they provide a robust defence against unwanted scrutiny.

5: Pursue Complete Anonymity

For those seeking the highest level of privacy, adopting a non-digital lifestyle may be necessary. This involves avoiding traceable devices, such as smartphones, modern vehicles, and smart home systems. Instead, rely on analogue tools and non-digital alternatives to minimize your exposure to tracking.

When identification is required, consider using passports instead of driver’s licenses, as they do not disclose your residential address. Additionally, avoid using credit cards or other traceable payment methods, opting instead for cash or cryptocurrencies that prioritize anonymity. Achieving complete anonymity demands significant lifestyle changes and constant vigilance. You may need to forgo many conveniences of modern life, including online services and connected devices. While this level of privacy is not practical for everyone, it remains an option for those with the dedication and resources to pursue it.

Taking Control of Your Digital Presence

Disappearing online and protecting your privacy is a challenging yet attainable goal. By implementing these steps, you can progressively reduce your digital footprint while balancing convenience and security. Whether your aim is to limit corporate surveillance or achieve complete anonymity, the process is deeply personal and depends on your specific needs and comfort level. Each action you take brings you closer to reclaiming control over your digital presence, empowering you to navigate the online world on your terms.

Media Credit: Proton