By D. Cooper

Is this the end for the consent pop-up?

An Irish civil rights group believes that it has successfully exposed the so-called legal fictions that underpin the online advertising industry. The Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL), says that Europe’s data protection regulators will soon declare the current regime illegal. At the heart of this complaint is both how the industry asks for permission, and then how it serves adverts to users online. Describing the situation as the “world’s biggest data breach,” the consequences of the ruling could have staggering ramifications for everything that we do online.

“The world’s biggest data breach”

Real-Time Bidding (RTB) is the mechanism by which most online ads are served to you today, and lies at the heart of the issue. Visit a website and, these days, you will notice a split-second delay between the content loading, and the adverts that surround it. You may be reading a line in an article, only for the text to suddenly leap halfway down the page, as a new advert takes its place in front of your eyes. This delay, however small, accommodates a labyrinthine process in which countless companies bid to put their advert in front of your eyes. Omri Kedem, from digital marketing agency Croud, explained that the whole process takes less than 100 milliseconds from start to finish.

Advertising is the lifeblood of the internet, providing social media platforms and news organisations with a way to make money. Advertisers feel more confident paying for ads, however, if they can be reasonably certain that the person on the other end is inside the target market. But, in order to make sure that this works, the platform hosting the ad needs to know everything it can about you, the user.

This is how, say, a sneaker store is able to market its wares to the local sneakerheads or a vegan restaurant looks for vegans and vegetarians in its local area. Companies like Facebook have made huge profits on their ability to laser-focus ad campaigns on behalf of advertisers. But this process has a dark side, and this micro-targeting can, for instance, be used to enable hateful conduct. The most notable example is from 2017, when ProPublica found that you could target a cohort of users deemed anti-semitic with the tag “Jew Hater.”

Every time you visit a website, a number of facts about you are broadcast to the site’s owner including your IP address. But that data can also include your exact longitude and latitude (if you have built-in GPS), your carrier and device type. Visit a news website every day and it’s likely that both the publisher and ad-tech intermediary will track which sections you spend more time reading.

This information can be combined with material you’ve willingly submitted to a publisher when asked. Subscribe to a publication like the Financial Times or Forbes, for instance, and you’ll be asked about your job title and industry. From there, publishers can make clear assumptions about your annual income, social class and political interests. Combine this information — known in the industry as deterministic data — with the inferences made based on your browsing history — known as probabilistic data — and you can build a fairly extensive profile of a user.

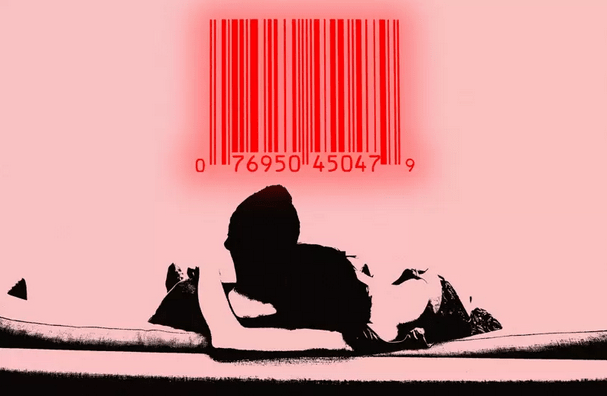

“The more bidders you have on something you’re trying to sell, in theory, the better,” says Dr. Johnny Ryan. Ryan is a Senior Fellow at the ICCL with a specialism in Information Rights and has been leading the charge against Real-Time Bidding for years. In order to make tracking-based advertising work, the publisher and ad intermediary will compress your life into a series of codes: Bidstream Data. Ryan says that this is a list of “identification codes [which] are highly unique to you,” and is passed on to a number of auction sites.

“The most obvious identification is the app that you’re using, which can be very compromising indeed, or the specific URL that you’re visiting,” says Ryan. He added that the URL of the site, which can be included in this information, can be “excruciatingly embarrassing” if seen by a third party. If you’re looking up information about a health condition or material related to your sexuality and sexual preferences, this can also be added to the data. And there’s no easy and clean way to edit or redact this data as it is broadcast to countless ad exchanges.

In order to harmonize this data, the Interactive Advertising Bureau, the online ad industry’s trade body, produces a standard taxonomy. (The IAB, as it is known, has a standalone body operating in Europe, while the taxonomy itself is produced by a New York-based Tech Lab.) The IAB Audience Taxonomy (subsequently revised to version 1.1) will codify you, for instance, as being into Arts and Crafts (Code 1472) or Birdwatching (435). Alternatively, it can tag you as having an interest in Islam (602), Substance Abuse (568) or if you have a child with special educational needs (357).

But not every bidder in those auctions is looking to place an ad, and some are much more interested in the data that is being shared. A Motherboard story from earlier this year revealed that the United States Intelligence Community mandates the use of ad-blockers to prevent RTB agencies from identifying serving personnel, data which could wind up in the hands of rival nations. Earlier versions of IAB’s Content Taxonomy even included tags identifying a user as potentially working for the US military.

It’s this specificity in the data, coupled with the fact that it can be shared widely and so regularly, that has prompted Ryan to call this the “world’s biggest data breach.” He cited an example of a French firm, Vectuary, which was investigated in 2018 by France’s data protection regulator, CNIL. What officials found was data listings for almost 68 million people, much of which had been gathered using captured RTB data. At the time, TechCrunch reported that the Vectaury case could have ramifications for the advertising market and its use of consent banners.

The issue of consent

In 2002, the European Union produced the ePrivacy Directive, a charter for how companies needed to get consent for the use of cookies for advertising purposes. The rules, and how they are defined, have subsequently evolved, most recently with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). One of the consequences of this drive is that users within the EU are presented with a pop-up banner asking them to consent to tracking. As most cookie policies will explain, this tracking is used for both internal analytics and to enable tracking-based advertising.

To standardize and harmonize this process, IAB Europe created the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF). This, essentially, lets publishers copy the framework laid down by the body on the assumption that they have established a legal basis to process that data. When someone does not give consent to be tracked, a record of that decision is logged in a piece of information known as a TC String. And it’s here that the ICCL has (seemingly) claimed a victory after lodging a complaint with the Belgian Data Protection Authority, the APD, saying that this record constitutes personal data.

A draft of the ruling was shared with IAB Europe and the ICCL, and reportedly said that the APD found that a TC String did constitute personal data. On November 5th, IAB Europe published a statement saying that the regulator is likely to “identify infringements of the GDPR by IAB Europe,” but added that those “infringements should be capable of being remedied within six months following the issuing of the final ruling.” Essentially, because IAB Europe was not treating these strings with the same level of care as personal data, it needs to start doing so now and / or face potential penalties.

At the same time, Dr. Ryan at the ICCL declared that the campaign had “won” and that IAB Europe’s whole “consent system” will be “found to be illegal.” He added that IAB Europe created a fake consent system that spammed everyone, every day, and served no purpose other than to give a thin legal cover to the massive data breach in at the heart of online advertising.” Ryan ended his statement by saying that he hopes that the final decision, when it is released, “will finally force the online advertising industry to reform.”

This reform will potentially hinge on the thorny question of if a user can reasonably be relied upon to consent to tracking. Is it enough for a user to click “I Accept” and therefore write the ad-tech intermediary involved a blank check? It’s a question that ad-tech expert and lawyer Sacha Wilson, a partner at Harbottle and Lewis, is interested in. He explained that, in the law, “consent has to be separate, specific, informed [and] unambiguous,” which “given the complexity of ad tech, is very difficult to achieve in a real-time environment.”

Wilson also pointed out that something that is often overstated is the quality of the data being collected by these brokers. “Data quality is a massive issue,” he said, “a significant proportion of the profile data that exists is actually inaccurate — and that has compliance issues in and of itself, the inaccuracy of the data.” (This is a reference to Article 5 of the GDPR, where people who process data should ensure that the data is accurate.) In 2018, an Engadget analysis of data held by prominent data company Acxiom showed that the information held on an individual can be often wildly inaccurate or contradictory.

One key plank of European privacy law is that it has to be easy enough to withdraw consent if you so choose. But it doesn’t appear as if this is as easy as it could be if you have to approach every vendor individually. Visit ESPN, for instance, and you’ll be presented with a list of vendors (listed by the OneTrust platform) that numbers into the several hundreds. MailOnline’s vendor list, meanwhile, runs to 1,476 entries. (Engadget’s, for what it’s worth, includes 323 “Advertising Technologies” partners.) It is not necessarily the case that all of those vendors will be engaged at all times, but it does suggest that users cannot simply withdraw consent at every individual broker without a lot of time and effort.

Transparency and consent

Townsend Feehan is the CEO of IAB Europe, the body currently awaiting a decision from the APD concerning its data protection practices. She says that the thing that the industry’s critics are missing is that “none of this [tracking] happens if the user says no.” She added that “at the point where they open the page, users have control. [They can] either withhold consent, or they can use the right to object, if the asserted legal basis is legitimate interest, then none of the processing can happen.” She added that users do, or do not, consent to the discrete use of their data to a list of “disclosed data controllers,” saying that “those data controllers have no entitlement to share your data with anyone else,” since doing so would be illegal.

[Legitimate Interest is a framework within the GDPR enabling companies to collect data without consent. This can include where doing so is in the legitimate interests of an organization or third party, the processing does not cause undue harm or detriment to the person involved.]

While the type of sharing described by the ICCL and Dr. Ryan isn’t impossible, from a technical standpoint, Feehan made it clear that to do so is illegal under European law. “If that happens, it is a breach of the law,” she said, “and that law needs to be enforced.” Feehan added that at the point when data is first collected, all of the data controllers who may have access to that information are named.

Feehan also said that IAB Europe had practices and procedures put in place to deal with members found to be in breach of its obligations. That can include suspension of up to 14 days if a violation is found, with further suspensions liable if breaches aren’t fixed. IAB Europe can also permanently remove a company that has failed to address its policies, which it signs up to when it joins the TCF. She added that the body is currently working to further automate its audit processes in order to ensure it can proactively monitor for breaches and that users who are concerned about a potential breach can contact the body to share their suspicions.

It is hard to speculate on what the ruling would mean for IAB Europe and the current ad-tech regime more broadly. Feehan said that only when the final ruling was released would we know what changes the ad industry will have to institute. She asserted that IAB Europe was little more than a standards-setter rather than a data controller in real terms. “We don’t have access to any personal data, we don’t process any data, we’re just a trade association.” However, should the body be found to be in breach of the GDPR, it will need to offer up a clear action plan in order to resolve the issue.

It’s not just consent fatigue

The issue of Real-Time Bidding data being collected is not simply an issue of companies being greedy or lax with our information. The RTB process means that there is always a risk that data will be passed to companies with less regard for their legal obligations. And if a data broker is able to make some cash from your personal information, it may do so without much care for your individual rights, or privacy.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Mobilewalla, an Atlanta-based ad-tech company, had enabled warrantless surveillance through the sale of its RTB data. Mobilewalla’s vast trove of information, some of which was collected from RTB, was sold to a company called Gravy Analytics. Gravy, in turn, passed the information to its wholly-owned subsidiary, Venntel, which then sold the information to a number of federal agencies and related partners.

This trove of information may not have had real names attached, but the Journal says that it’s easy enough to tie an address to where a person’s phone is placed most evenings. And this information was, at the very least, passed on to and used by the Department of Homeland Security, Internal Revenue Service and US Military. All three reportedly tracked individuals both in the US and abroad without a warrant enabling them to do so.

In July 2020, Mobilewalla came under fire after reportedly revealing that it had tagged and tracked the identity of Black Lives Matter protesters. At the time, The Wall Street Journal report added that the company’s CEO, in 2017, boasted that the company could track users while they visit their places of worship to enable advertisers to sell directly to religious groups.

This sort of snooping and micro-targeting is not, however, limited to the US, with the ICCL finding a report made by data broker OnAudience.com. The study, a copy of which it hosts on its website, discusses the use of databases to create a cohort of around 1.4 million users. These people were targeted based on a belief that they were “interested in LGBTQ+,” identified because they had searched for relevant topics in the prior 14 days. Given both the unpleasant historical precedent of listing people by their sexuality and the ongoing assault on LGBT rights in the country, the ease at which this took place may concern some.

Looking to the future

On November 25th, the APD announced that it had sent its draft decision to its counterparts in other parts of Europe. If the procedure doesn’t hit any roadblocks, then the ruling will be made public around four weeks later, which means at some point in late December. Given the holidays, we may not see the likely fallout — if any — until January. But it’s possible that either this doesn’t make much of a change in the ad landscape, or it could be dramatic. What’s likely, however, is that the issues around how much a user can consent to having their data used in this manner won’t go away overnight.

Feature Image Credit: #Urban-Photographer via Getty Images