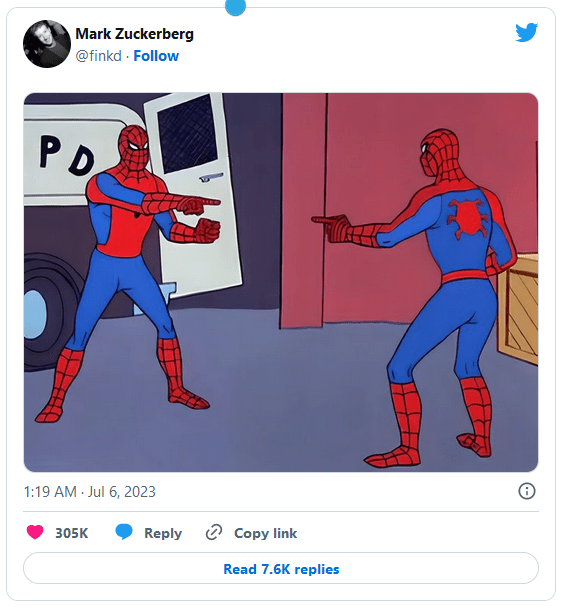

The scene from which the meme is derived, though, gets at what I think is really going on: the Spider-Man on the right is Charles Cameo, an imposter who uses disguises to steal art treasures. To extend the analogy, Threads looks like Twitter at first glance, but is in fact something much different — and what it is stealing is certainly what Elon Musk and Twitter have always wanted:

The important takeaway is that all of the levels of the meme are connected: Threads looks like Twitter, but its essential differences are almost certainly table-stakes in being something larger than Twitter ever was. The question is if that treasure is itself a mirage.

The Social/Communications Map of 2013

Back in 2013 I created The Social/Communications Map:

That map came out of an Article called The Multitudes of Social that argued that social media was not a single category destined to be won by a single app, and that Facebook could never “own social”:

The very idea of owning social is a fool’s errand. To be social is to be human, and to be human is, as Whitman wrote, to contain multitudes. Multitudes of apps, in my case…

Facebook needs to appreciate that their dominance of social on the PC was an artifact of the PC’s lack of mobility and limited application in day-to-day life. Smartphones are with us literally everywhere, and there is so much more within us than any one social network can capture.

The point about there being a multitude of ways to communicate online has held up well; I think, though, the axis about permanence versus ephemerality was less important than it seemed when the big battle was between Facebook and Snapchat. A better axis leans into the “SocialCommunications” aspect of the title: the most important new social networks of the last few years have been notable for not really being social networks at all.

I’m referring to the TikTok-ization of user-generated content: the reason why TikTok was such a blindspot for Facebook is that, unlike Snapchat, it doesn’t depend on network effects, but rather abundance. One of the first times I wrote about TikTok was in the context of Quibi, the failed mobile video app from Hollywood impresario Jeffrey Katzenberg:

The single most important fact about both movies and television is that they were defined by scarcity: there were only so many movies that would ever be made to fill only so many theater slots, and in the case of TV, there were only 24 hours in a day. That meant that there was significant value in being someone who could figure out what was going to be a hit before it was ever created, and then investing to make it so. That sort of selection and production is what Katzenberg and the rest of Hollywood have been doing for decades, and it’s understandable that Katzenberg thought he could apply the same formula to mobile.

Mobile, though, is defined by the Internet, which is to say it is defined by abundance…So it is on TikTok, or any other app with user-generated content. The goal is not to pick out the hits, but rather to attract as much content as possible, and then algorithmically boost whatever turns out to be good…The truth is that Katzenberg got a lot right: YouTube did have a vulnerability in terms of video content on mobile, in part because it was a product built for the desktop; TikTok, like Quibi, is unequivocally a mobile application. Unlike Quibi, though, it is also an entertainment entity predicated on Internet assumptions about abundance, not Hollywood assumptions about scarcity.

It’s ultimately a math question: are you more likely to find compelling content from the few hundred people in your social network, or from the millions of people posting on the service? The answer is obviously the latter, but that answer is only achievable if you have the means of discovering that compelling content, and, to be fair to both Facebook and Twitter, the sort of computational power necessary to pull off a TikTok-style network didn’t exist when those companies got started.

The Social/Communications Map of 2023

Set that point about time of origin aside just for a moment; here is what I think a better representation of the Social/Communications Map looks like in 2023:

The first change is that the symmetric/asymmetric axis has been replaced by the nature of the sorting algorithm: chronological order versus algorithmic selection. However, this isn’t that big of a change; consider messaging, which is by definition about symmetric social networking. Messaging only really makes sense if it is organized by time — imagine trying to carry on a conversation if every message you saw were algorithmically selected, instead of simply displayed in order. Algorithmic sorting, though, makes much more sense when you are consuming content that is broadcast to the world, and thus has no assumptions about or expectations for in-order contextual replies.

The second change is the TikTok-ization I noted above: my new vertical axis is user-generated content, by which I mean content across the network, versus network-generated content, by which I mean content from the people you choose to follow. If you maintain the same public/private distinction I had in the original, you get a landscape that looks something like this (note that Facebook is better thought of as a private social network, given that the default nature of posts is that they are only seen by those in your network).

This is where the bit above about historical time comes in: another way to look at this map is as a representation of how content on the Internet has evolved; the early web, and early forms of user-generated content like forums and blogs, were and are still located in the upper left. This quadrant is fairly decentralized, and is Aggregated by Google and search.

The lower left quadrant came next: one site held all of the content from your network, and presented it chronologically. Some sites, like Twitter and Instagram, stayed here for years; Facebook, though, quickly jumped ahead to the lower right quadrant, and organized your feed algorithmically. This quadrant became the other major pillar of Internet advertising (along with search): figuring out what content to show you from your network wasn’t too dissimilar of a problem from figuring out what ads to show you, and the nature of a dynamically-generated feed that was unique to every individual was something that was only possible with digital media.

The final stage is, as noted, represented by TikTok: once again your network doesn’t matter, because the content comes from anywhere. This world, though, unlike the open web, is governed by the algorithm, not time or search.

Twitter, Threads, and the Upper-Right

I was honestly surprised to find out that both Twitter and Instagram were in the lower left quadrant until 2016; that is when both services started offering an algorithmic timeline. Of course the surprise for the two services ran in the opposite direction: for Twitter it’s amazing that the company managed to change anything at all, and for Instagram it’s a surprise the service stayed the same for so long. Since then Instagram has heavily invested in its direct messaging product even as it has slowly abandoned the public parts of the lower left: everything is an algorithm and, with Reels, completely disconnected from your network.

Perhaps the starkest change that Musk has made to Twitter, meanwhile, has been a headlong rush into the upper right: the “For You” tab is far more aggressive about promoting tweets from people you don’t follow, and it’s increasingly impossible to escape; the app always defaults to “For You”, and there are no more 3rd-party app alternatives. Eugene Wei argues this has blown up the timeline and ruined the Twitter experience:

What established the boundaries of Twitter? Two things primarily. The topology of its graph, and the timeline algorithm. The two are so entwined you could consider them to be a single item. The algorithm determines how the nodes of that graph interact. In a literal sense, Twitter has always just been whose tweets show up in your timeline and in what order.

In the modern world, machine learning algorithms that mediate who interacts with whom and how in social media feeds are, in essence, social institutions. When you change those algorithms you might as well be reconfiguring a city around a user while they sleep. And so, if you were to take control of such a community, with years of information accumulated inside its black box of an algorithm, the one thing you might recommend is not punching a hole in the side of that black box and inserting a grenade. So of course that seems to have been what the new management team did. By pushing everyone towards paid subscriptions and kneecapping distribution for accounts who don’t pay, by switching a TikTok style algorithm, new Twitter has redrawn the once stable “borders” of Twitter’s communities.

This new pay-to-play scheme may not have altered the lattice of the Twitter graph, but it has changed how the graph is interpreted. There’s little difference. My For You feed shows me less from people I follow, so my effective Twitter graph is diverging further and further from my literal graph. Each of us sits at the center of our Twitter graph like a spider in its web built out of follows and likes, with some empty space made of blocks and mutes. We can sense when the algorithm changes. Something changed. The web feels deadened.

I’ve never cared much about the presence or not of a blue check by a user’s name, but I do notice when tweets from people I follow make up a smaller and smaller percentage of my feed. It’s as if neighbors of years moved out from my block overnight, replaced by strangers who all came knocking on my front door carrying not a casserole but a tweetstorm about how to tune my ChatGPT and MidJourney prompts.

Instagram’s Evolution has shown that this shift is possible, but the shift has been systemic and gradual — and even then subject to occasionally intense pushback. Musk’s Twitter, though, has been haphazard and blistering in its pace. What ought to concern the company about Threads, though, is the possibility that all of the upheaval — which effectively sacrifices the niche Twitter had carved out amongst text nerds that dominate industries like media — will not actually result in the user growth Musk is hoping for, because Threads got there first.

Indeed, this map is the key to understanding why it is that Threads looks like Twitter, but is in fact a very different product: Threads is solidly planted in the upper right. When you log onto the app for the first time, your feed is populated by the algorithm; there is some context given by whom you follow on Instagram, but Meta seems aware that accounts you might want to look at may be different than accounts you want to hear from, and is thus filling the feeds with what it thinks you might find interesting. That is how it can provide an at-least-somewhat-compelling first-run experience to 100 million people in five days.

Twitter, on the other hand, faces the burden of millions having tried the service in past iterations and quickly deciding it wasn’t for them; even if the algorithm were effective, it may already be too late to gain new users, even as you sacrifice what the service’s existing users preferred.

The Threads Experiment

This leads to the biggest open question about Threads’ long-term prospects, and, by extension, Twitter’s: did those millions of abandoned Twitter users give up because text-based social networking just wasn’t that interesting to them, or because Twitter made it too hard to get started? I’ve made the case that it’s the former, which means that Threads is a grand experiment as to the validity of that thesis. If those 100 million users stay engaged (and if that number continues to grow), then the people chalking up Twitter’s inability to grow or monetize effectively to the company’s inability to execute are correct.

At the same time, as Wei notes, Musk’s tenure has highlighted the problems with doing too much: what if Twitter succeeded to the extent it did not despite management’s seeming ineffectiveness, but because of it?

I’ve written before in Status as a Service or The Network’s the Thing about how Twitter hit upon some narrow product-market fit despite itself. It has never seemed to understand why it worked for some people or what it wanted to be, and how those two were related, if at all. But in a twist of fate that is often more of a factor in finding product-market fit than most like to admit, Twitter’s indecisiveness protected it from itself. Social alchemy at some scale can be a mysterious thing. When you’re uncertain which knot is securing your body to the face of a mountain, it’s best not to start undoing any of them willy-nilly. Especially if, as I think was the case for Twitter, the knots were tied by someone else (in this case, the users of Twitter themselves).

Many of those knots are tied to that lower left quadrant: a predominantly time-based feed makes sense if a service is predominantly about “What is happening?”, to use Twitter’s long-time prompt; a graph based on who you choose to follow doesn’t just show what you want to see, it also controls what you don’t (Wei notes that this is a particularly hard problem for algorithmically generated feeds). Both qualities seem particularly pertinent for a medium (text) that is information dense and favored by people interested in harvesting information, a very different goal than looking to pass the time with an entertaining video or ten.

It follows, then, that Twitter’s best defense against Threads may be to retreat to that lower left corner: focus on what is happening now, from people you chose to follow. The problem, though, is that while this might win the battle against Threads, it means that Musk will have lost the war when it comes to ever making a return on his $44 billion. In truth, though, that war is already lost: Musk’s lurch for the upper right was probably the best path to reigniting user growth, but if that is the corner that matters then Threads will win.

Thread’s Chronological Timeline

The other question is if Threads will come for Twitter’s place on the map; Head of Instagram Adam Mosseri says that a chronological timeline is coming:

Placing this option in the context of Facebook and Instagram actually suggests that this feature won’t matter very much; both services make it hard to find, and revert back to the default algorithmic feed, and for good reason: users may say they want a chronological feed, but their revealed preference is the opposite. Instagram founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, who initially opposed algorithmic ranking in Instagram, told me in a Stratechery Interview:

Kevin Systrom: I remember thinking when the team was like, “We’re thinking of using machine learning to sort the Explore page,” I’m not even sure what they call it now, but basically the Explore page and I remember saying, “It just feels like that’s a bunch of hocus-pocus that won’t work. Or maybe it’ll work but you won’t really understand what it’s doing and you won’t fully understand the implications of it, so we should probably just keep it very simple.” I was so wrong and I only remember it because I was so wrong, but you asked about feed, Mike would probably give you his anecdote about feed. But on the Explore page I was very anti and then I think I became pro only once I saw what it could do. Not in terms of just usage metrics, but just the quality of what people were served compared to some of our heuristics before…

Mike Krieger: I’ll share a funny anecdote about the Explore experiment. Facebook has all these internal A/B testing tooling and we hooked into it and we ran our first machine learning on the Explore experiment and we filed a bug report and I’m like, “Hey, your tool isn’t working, that’s not reporting results here.” And they said, “No, the results are just so strong that they’re literally off the charts. The little bars that show it literally is over 200%, you just should ship this yesterday.” The data looked really good.

That noted, observe Mosseri’s stated goal for the app, as articulated to Alex Heath of The Verge:

I think success will be creating a vibrant community, particularly of creators, because I do think this sort of public space is really, even more than most other types of social networks, a place where a small number of people produce most of the content that most everyone consumes. So I think it’s really about creators more than it is about average folks who I think are much more there just to be entertained. I think [we want] a vibrant community of creators that’s really culturally relevant. It would be great if it gets really, really big, but I’m actually more interested in if it becomes culturally relevant and if it gets hundreds of millions of users. But we’ll see how it goes over the next couple of months or probably a couple of years.

“Culturally relevant” is the one game that Twitter has won, far more than Facebook, and arguably more than Instagram: Twitter drives national and international media coverage, from TV to newspapers, to an extent that drastically exceeds its monetization potential. Meta, meanwhile, has been content to provide social networking for the silent majority, making tons of money along the way. The best way to do that with text — if it is even possible — would be to stay in that upper right corner; cultural relevancy, though, is still in the bottom left, even if there aren’t nearly as many users, or money.

And, it must be noted, Twitter is vulnerable in its home territory; I’ve long argued that the importance of convenience in terms of app success is underrated (see Threads starting with your Instagram sign-in and network), but its hard to think of anything that might motivate users to make a change more than resolving cognitive dissonance. There is a sizable segment of that culturally relevant audience Mosseri wants to capture who are opposed to Musk, and yet can’t give up Twitter; I suspect that much of the outpouring of glee over Threads’ early success is from this cohort that wants nothing more than non-Musk Twitter.

Ultimately, though, I think they may be disappointed: Meta is about algorithms and scale, and I would bet that Threads will leave real time reactions, news, and pitched battles to Twitter; Musk’s most important decision may be accepting that that is enough, because it’s all he’s going to get.