The biggest ads from the biggest brands in big TV moments used to be dominated by cars, candy, and beer. Now—like everything else—it’s Big Tech.

For 32 years, USA Today’s Ad Meter has measured the popularity of Super Bowl ads, and this year’s list looked different than ever before.

Google nabbed the No. 3 spot, Amazon No. 7, and Microsoft No. 9. Even Facebook, which ranked much lower at No. 39, was airing its first-ever Super Bowl spot but still managed to beat out such TV ad stalwarts as GMC, Audi, Coke, and Pepsi.

Seemingly out of nowhere (although after years of building up to it), Big Tech has finally become the kind of major TV-advertiser class that used to be the sole domain of legacy brands—those TV ad staples in such popular categories as autos, beer, and candy. For most of their history, these companies scoffed at traditional media. Can’t measure it, can’t convert viewers into customers, not enough real-time data. Yet here are the 21st century’s most dominant brands behaving like their counterparts of the late 20th, using TV as a key tool to build image and consumer loyalty. Taking a half-step back, this development is a bit rich given that other than Microsoft, these are companies whose businesses are working, through digital advertising dominance and streaming content, essentially to destroy the modern TV industry.

The Super Bowl and most other high-profile TV opportunities like the Oscars and Grammys are now where the biggest tech companies go to forge the kind of emotional relationship with consumers that helps prevent us from becoming too critical, too nervous, and too creeped out by their actions.

It could not have been scripted better.

Big spenders

Microsoft was one of the biggest TV ad spenders in tech last year, shelling out half a billion dollars. On its Surface brand alone, the company boosted ad spending by almost 20%, to an estimated $219.1 million, according to measurement firm iSpot.

Amazon spent more than $1.25 billion overall in 2019, boosting TV ad spending for Prime, for example, by a massive 487% to hit about $210 million. Also notable for Amazon, it more than doubled TV ad spending on its home security system Ring, hitting about $79 million in 2019, compared with $32 million in 2018. Given that the company was recently accused of providing user data to Facebook and other companies without making Ring users aware that their data was being shared, adding to its other privacy scandals, it’s going to need all the brand loyalty it can muster.

Facebook is the smallest of the big tech companies, and it correspondingly spent just $300 million on TV marketing last year, with more than half of it, according to iSpot, going to burnish Facebook’s brand.

The ads, the strategies

After Google ran its Super Bowl ad on Sunday night, Twitter lit up with posts about its emotional effectiveness.

Microsoft received similar kudos for its ad profiling 49ers assistant coach Katie Sowers, which hit the perfect balance of product, brand, and a message of female empowerment that Secret and Olay, both of which have been marketing to women for as long as they’ve existed, couldn’t manage to find.

Amazon was back at its goofy celebrity best, this time teaming with Ellen DeGeneres to wonder what life was like before Alexa.

And then Facebook dropped in with an homage to eclectic Groups, with a side dish of Sly Stallone and Chris Rock.

All the game needed to have a Big Tech full house was Apple, but even Cupertino managed to launch a new spot yesterday for its Arcade video game subscription service.

Anyone wondering why the planet’s biggest and most successful tech and digital media companies are increasingly turning to good old-fashioned TV ads need look no further for a reason than what comedian and talk-show host Desus of Desus and Mero had to say:

As I wrote on Sunday, Facebook made its users the focus of its Super Bowl ad to draw as much attention as possible away from its myriad of corporate issues. Each of the companies chose the largest advertising stage and its most strategic products—Facebook Groups, Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft Surface, Google Search—as the device with which to build a narrative and emotional connection with users.

Back in 2018, Google CMO Lorraine Twohill heralded the brand’s ads “Parisian Love” (which became Google’s first-ever Super Bowl ad) and “Dear Sophie” as the spark for what’s become the company’s strategy around humanizing its products and itself. When she joined the company in 2009, the marketing formula was more tech nerd than Mad Men and went something like this: We have to launch a new product, here’s a blog post, and here is a video of the product manager explaining its features. Please watch the video.

“In the early days, we had a Chrome digital-only campaign, which was about three things: safety, simplicity, and speed. Very rational,” said Twohill. “That did get us so far, but no one gets out of bed in the morning and says, ‘I need a new browser.’ What changed the game for us was to go out and create ‘The web is what you make of it,’ which is essentially a brand campaign about people using the web to make their lives better.”

Replace “web” with soap, cars, beer, insurance, or burgers and it becomes pretty clear that these companies we see as among the most innovative in the world still rely upon some of the most hardy advertising tropes in existence. Amazon’s humor is no different than VW in 2011’s “The Force” that charmed us all just before the company’s reputation imploded under the emissions scandal. Or how Snickers uses it to avoid us looking too closely at the sustainability and labor challenges of the chocolate industry. Facebook’s Groups spot is the direct descendant of any commercial gleefully celebrating human gathering, from McDonald’s “You Deserve A Break Today” back in the ’80s, to the longstanding idea of Miller Time.

Microsoft’s Super Bowl ad was fantastic, but let’s face it, the point was Sowers’s story and her accomplishment, not a tablet computer, and could’ve easily been a spot for paper towels. Kind of like P&G’s long-running “Thank You, Mom” Olympic campaign. And while Google’s “Loretta” expertly uses its own products to make those human connections, it hinges on tying human connection and emotion to the brand, a tactic perfected in spots like Coke’s classic “Hilltop” and Budweiser’s “Puppy Love.”

Back then, we were being charmed by companies that we knew—or had some sense—that they were connected to such serious problems as obesity, pollution, addiction, and more. Those, of course, still remain, but say what you want about beer or fast-food burgers, they don’t lead to issues of data privacy and misinformation, among others.

The emotional connections forged by these ads seek to paper over all of that, at least for 30 seconds at a time.

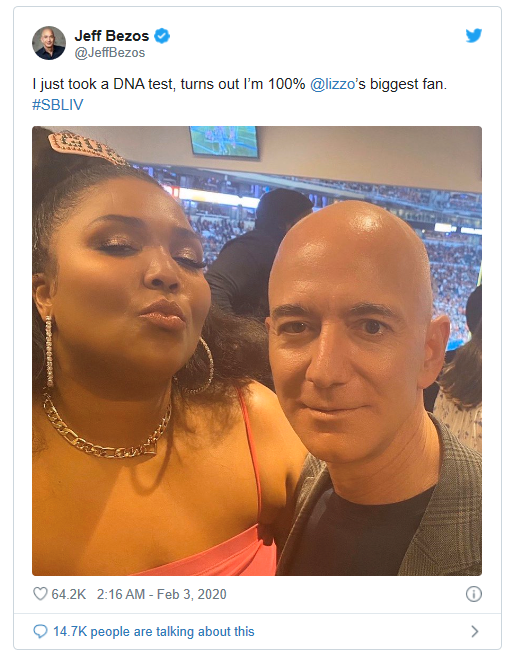

Oh, and add in a CEO tweet for good measure.

What’s next

These challenges—and Big Tech’s need to cultivate as much goodwill as possible—aren’t going anywhere, so expect this type of TV ad spending to continue to grow, at least until they actually do kill broadcast TV. This will be most acute during major events like the Super Bowl, Oscars, World Series, and anywhere else our fragmented media culture manages to come together in anything even remotely resembling a collective cultural experience. The more we love their ads, the more likely we’ll be to buy and use their products, and therefore less likely to address potential concerns, vote to have monopolies broken up, or otherwise question their motives.

On the bright side, though, at least Big Tech didn’t try to sell us a baby peanut.

By Jeff Beer.