To mark the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, creative agency And Us has devised the world’s first interactive street view of a war zone. Here’s how.

On February 24, 2022, Vladimir Putin waged an illegal war with Ukraine, inflicting mass devastation on the country, resulting in thousands of deaths and millions of innocent displaced people. In the year that has passed, a ravaged Ukraine is totally unrecognizable.

“There’s been quite a clear pattern of targeting civilian areas,” says Jamie Kennaway, executive creative director at And Us. “We had the idea of bringing it to life in a way that people can explore and see in a visceral way. It brings it home in a different way.”

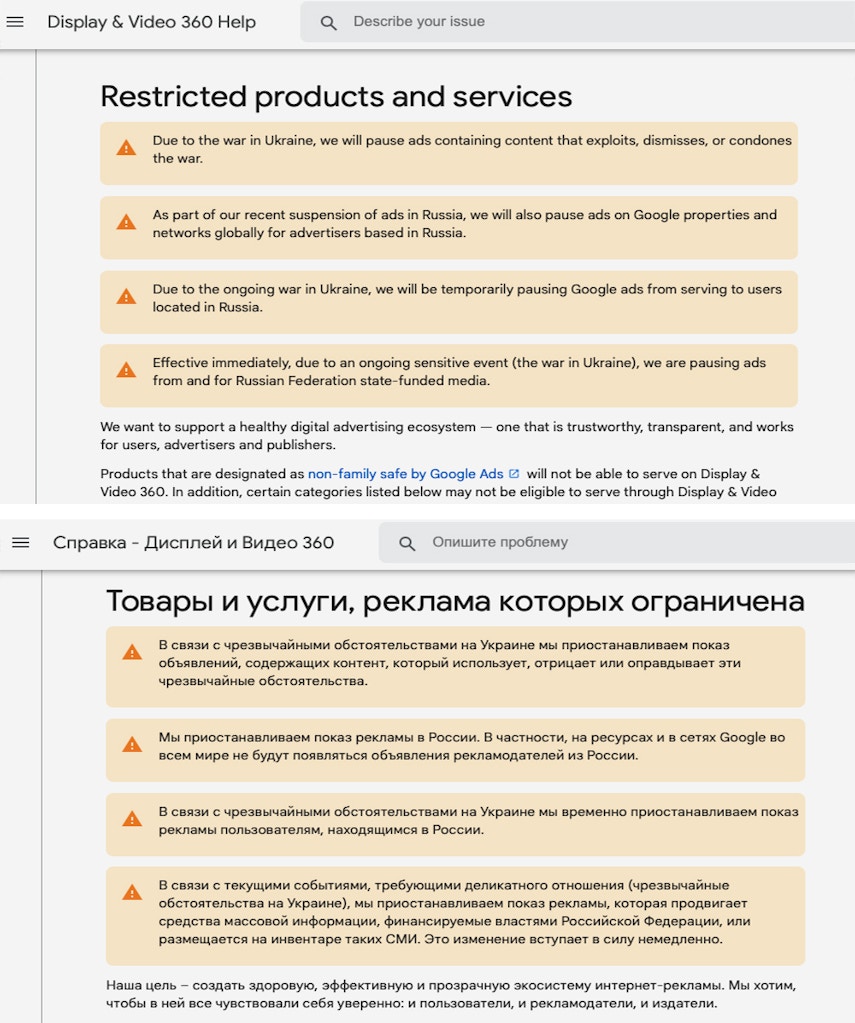

“Whether it was Yemen or Iraq, there’s never been an accurate representation of a war-torn country [on Google Street View]. [Google], understandably, don’t want to show violence.” With this in mind, just how difficult would it be to get someone on the ground to document the conflict?

Through previous projects, the indie agency had a network of people that could help. Diego Borges, the agency’s tech director, was able to connect with an exec working at Google Street View who, in turn, happened to know someone that was in Ukraine at the time who could get images. From the beginning, the duo says that the entire project has been both serendipitous and scary.

Taking a Street View car camera through an active war zone is obviously not an advisable plan, admits Kennaway. There were many times they would be on the phone with their Ukrainian contact and he was in an area that was under attack or experiencing power cuts. With a project like this, there are always going to be trepidations, no matter how important the cause is. “We didn’t want to put anyone at risk and we don’t put anyone at risk from a security point of view either,” he adds, stating clearly that the photographer and agencies safety was always front of mind.

Potential issues with Google were also a consideration as the photographer had previously worked with the tech giant and had been supplied with equipment under strict conditions. After talks, they came to an agreement. “There’s a situation on the ground that people need to see.”

The original plan was to get their Ukrainian partner there with a remote-controlled armored car fitted with cameras and drones. But in the planning stages, the photographer suggested using the masses of footage he had on file from his posting in Ukraine. Quickly, the creatives realized they could use scenes from various cities and not just one “symbolic area” in order to give an accurate representation of what was really happening on the ground. They could show the real devastation in Kyiv, Irpin, Kharkiv, Izyum and Cherigiv and Sumy.

“There’s no bigger documentation of what is happening,” says Kennaway. “There’s lots of other footage like drone shots, stuff on CNN and the BBC, a clip here and something there, but to say, come see for yourself, essentially, we realized that the angle was that we were asking people to bear witness.” This, he adds, has been important throughout horrific events in history and is extremely powerful.

For the immersive user journey itself, the team wanted to show what seemed to be the “deliberate targeting of civilian areas” and to highlight that they were “accessing something that was quite obviously a crime.” The notion of their being an undeniable truth eventually led the team to the frank campaign name.

“Obviously mistruth is a weapon of war. You take the camera down the street and it goes up onto this, there’s something very raw and untouched about it.” Looking through the before and after images were shocking, they say.

The end result is a dedicated website that allows the user to make their way through the streets of the chosen six Ukrainian cities, similar to Google Maps. By zooming in and looking around, people get a full 360 view of the devastation inflicted upon those areas.

But to guarantee the project would be seen by millions, the agency needed the backing of a client. “There’s a bit of virtue signaling. There’s a lot of stuff going on [there], versus actual people and institutions on the ground who are trusted with where the money goes,” he said. The more they spoke with Ukrainians on the ground, the more they realized some ‘charities’ were not as trusted or helpful as others.

This meant laborious research and a vetting process to ensure the partners they brought on were valid and doing vital work on the ground. The collective includes President Zelenskyy’s United24 initiative), Voices of Children, which offers long-term psychological support to children affected by war, plus Nova Ukraine and Vostok-Sos, both provide humanitarian supplies. Specifically, feedback from United24 suggested that they get approached constantly to partner on projects and they don’t go with everything. “We weren’t relying on United24, it was just a big surprise that in the end, they wanted to partner. We weren’t expecting that.”

The campaign rollout was decided early on, with a huge emphasis on the press and social media. “It is essentially a carrot that we’re going to give PR for the wider conversation,” admits Kennaway. He says they sought advice to see if it was “PR-able” and if not, they might have reconsidered what they were doing because that was the one chance it had and nobody has a “billion dollars of media money.”

“We’re going to try and get this through mainstream media and obviously the marketing world I mean, I was a bit hesitant about marketing media at first, but we said to our clients that marketing media is important because we can get it spreading in a different way, in different load channels that will also then give it exposure.”

Kennaway is super conscious that he doesn’t want this project to come off as all about the agency, which would feel wrong. The initiative itself has to lead, he wants people to see the efficacy of it and why it’s important. It’s about the “causes involved, the story behind it, and maybe some of the technicality,” he concludes.

“We’re just the puppeteers.”