Comparison charts help us make choices – but it isn’t always the correct choice, warns Rory Sutherland.

For the most part, marketers are not qualified to comment on possible miscarriages of justice in the trial of Lucy Letby. Few of us have any qualifications in neonatology, and I doubt many of us have read the transcript of the trial.

However, there is one area where many of us might be called on to act as expert witnesses in any future retrial: to testify on the uses and abuses of the comparison chart.

Below was the chart used in the trial to suggest that there was an unusually high correlation between the nurse’s presence on the ward and the incidence of suspicious deaths. It is now the subject of intense debate among statisticians, many of whom suggest that the frame of comparison is misleading. For instance, occasions where suspicious deaths occurred when she was not present were omitted from the table.

For those who need reminding, this is a comparison chart often used in marketing.

Both these charts absolutely fascinate me because they are, at varying times, both incredibly useful and totally misleading.

They are useful to consumers (and consequently to sellers) because, in many situations, it is impossible to make a confident purchase decision when presented with two or more options without being able to perform a side-by-side comparison.

Brands that offer consumers a portfolio of variations on the same theme – think Dyson or BMW – are always at risk of losing a customer who would have been happy with several of the options had they been presented singly, only to end up not buying any because they cannot decisively pick which of the acceptable options is best for them.

One reason I often buy second-hand cars is that the decision is usually easier: do I want this car or not? When configuring a new car, I am sometimes literally and metaphorically blinded by the headlights. Do I want to spend an extra £500 on active-matrix LED technology, or would I prefer the ventilated seats?

You can present consumers with too many acceptable choices, creating paralysis in place of decisiveness.

I’m told that the paradox-of-choice issue is also one of the surprising downsides of engaging in a threesome or orgy. There are plenty of attractive options, but it is difficult to know what position to adopt at any given moment.

Whenever people need to choose between options, they need to see the information all in one place, so side-by-side comparison is often essential. People cannot contentedly book a premium economy air ticket unless they know what the economy ticket would have cost – an insight that made one of our clients many millions of pounds.

But the very act of comparison also introduces a mental bias, in that it focuses your mind disproportionately on points of difference rather than areas of similarity.

In presenting side-by-side comparisons clearly, the comparison chart is an invaluable tool. But it is also a marvellous – and highly lucrative – device for misleading people.

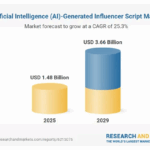

Consider a typical comparison chart for three classes of car.

Let’s call them the L, the GL and the GLX GT, priced respectively at £30,000, £45,000 and £60,000.

Typically, the chart will show two meager features possessed by the L (heated seats, automatic wash-wipe), then add another four features for the GL (leather seats, premium infotainment system, etc) and put a full column of 16 green ticks for the GLX.

None of this is entirely inaccurate or dishonest, but it is highly misleading – which is why marketers rather like it, especially as there is much more margin to be had on a premium product. You have focused the buyer’s attention disproportionately on the points of difference, not on the points of similarity.

“Oh look,” you think, “I get eight times as much stuff for only twice the money” (the GLX). Or, if you are torn between the L and the GL, you think, “Well, it’s only 50% more for three times more stuff. Ker-ching.”

But this is not so. A truly accurate comparison chart would list all the items you get with all three cars – wheels, tyres, folding rear seats, windscreen wipers, doors, windows, the lot. Then you would see that the base model L is perhaps better value after all, because it gives you 97% of the stuff for half the price of the GLX.

As with the information presented to the Lucy Letby jury, you can often cherry-pick data to make a very convincing case by leaving out contradictory information, or by focusing people’s attention on a narrow discrepancy shorn of its wider context. Lucy Letby had just bought a house (to me, one of the most surprising findings from the trial – that there are still parts of the UK where a nurse can afford to buy a house) and was working long hours to pay for the mortgage. There were also unexpected deaths where she was not present, but these were excluded from the comparison chart to produce a clean line of green ticks.

Forgive me another aside. I often think about this when I book air travel. I sometimes pay twice the price to enjoy a slightly bigger seat, lounge access and an extra piece of hand baggage. When I make that decision, I am thinking about the seat, the lounge and the baggage. But as Daniel Kahneman observed: “Nothing in life matters quite as much as you think it does while you are thinking about it.”

Looked at dispassionately, the really amazing part of air travel is the fact that you can travel at 600mph in a pressurized metal tube, with expert pilots and sensational technology. The seat and the lounge are perhaps only 10% of the value. But for whatever reason, I don’t think of it like this at all.

There is a wider philosophical question here. How often are decisions swayed not by an ultimate assessment of value but by ease of comparative judgment? As a marketer, I hope the answer is “rather a lot”. But in wider life, this is surely a problem.

Unrepresentative data is incredibly valuable for winning arguments. For really solving problems, just remember, it is often the data you don’t see that can crack the case.

By Rory Sutherland

Get in touch with Rory on LinkedIn