By Nathan Hurst

The Faustian bargain that has us trading private data for free services from the likes of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google is finally getting attention from regulators and lawmakers.

Cambridge Analytica. Russian hackers and election meddling. The Equifax data breach. Fake news. Twitter and Instagram harassment. Facebook mining our personal data and—best-case scenario—unabashedly using it to sell us stuff.

What’s a society to do? Ours has begun clamoring for boycotts and regulation, even for breaking up the biggest tech giants. For a decade (or two), the tech industry, led by the largest, most successful companies, has painted attempts to regulate it as stifling innovation; an impediment to the new, utopian “tech will solve everything” system these benevolent founders seek to build. Maybe that’s true, but considering the aforementioned abuses, the “Don’t be evil” edict seems to hold less water, and #deletefacebook might finally be having its moment.

Presidential candidates have made trust-busting a part of their platforms. Europe and California have instituted legislation designed to allow citizens greater control over their personal data and how it’s used. Other states are following suit, buoyed by bipartisan support. It feels like major tech regulation is coming, but whether it’s a culmination of decades of regulatory decisions or just a step on the path is unclear.

‘Free’ Isn’t Free

You probably know some of the basics of how internet advertising targets its viewers. Sometimes, ads might seem a little too relevant, leading you to wonder whether your phone is listening to your conversations. You feel uneasy about it, even as you admit that you’d rather see ads for stuff you like than for something completely uninteresting to you. From the advertisers’ perspective, it’s much more efficient to target just a few people and make sure those people see their ads rather than waste time and money putting ads in front of people who don’t need or care about what they’re selling. The companies that do this can even track whether a user who has seen a particular ad then visits the store in question.

We’ve settled into a “freemium” model: In exchange for our data, we get to use free services, including email and social media. This is how companies such as Facebook make money and still provide us with the services we enjoy (although research has shown that spending more time on Facebook makes you less happy, rather than more).

(Image: Ink Drop/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: Ink Drop/Shutterstock.com)

But there’s more than one reason to be concerned about letting our personal data be sucked up by tech companies. There are many ways the wholesale gathering of data is being abused or could be abused, from blackmail to targeted harassment to political lies and election meddling. It reinforces monopolies and has led to discrimination and exclusion, according to a 2020 report from the Norwegian Consumer Council. At its worst, it disrupts the integrity of the democratic process (more on this later).

Increasingly, private data collection is described in terms of human rights—your thoughts and opinions and ideas are your own, and so is any data that describes them. Therefore, collection of it without your consent is theft. There’s also the security of all this data and the risk to consumers (and the general public) when a company slips up and some entity—hackers, Russia, China—gets access to it.

“You’ve certainly had a lot of political chaos in the US and elsewhere, coinciding with the tech industry finally falling back to Earth and no longer getting a pass from our general skepticism of big companies,” says Mitch Stoltz, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “If so many people weren’t getting the majority of their information about the world from Facebook, then Facebook’s policies about political advertising (or most anything else) wouldn’t feel like life and death.”

Policy suggestions include the Honest Ads Act, first introduced in 2017 by Senators Mark Warner and Amy Klobuchar, which would require online political ads to carry information about who paid for them and who they targeted, similar to how political advertising works on TV and radio. This was in part a response to the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2016.

Cambridge Analytica Blows Up

It’s easy to beat up on Facebook. It’s not the only social network with questionable data-collection policies, but it is the biggest. Facebook lets you build a personal profile, connect that profile to others, and communicate via messages, posts, and responses to others’ posts, photos, and videos. It’s free to use, and the company makes its money by selling ads, which you see as you browse your pages. What could go wrong?

In 2013, a researcher named Aleksandr Kogan developed an app version of a personality quiz called “thisisyourdigitallife” and started sharing it on Facebook. He’d pay users to take the test, ostensibly for the purposes of psychological research. This was acceptable under Facebook policy at the time. What wasn’t acceptable (according to Facebook, although it may have given its tacit approval, according to whistleblowers in the documentary The Great Hack) was that the quiz didn’t just record your answers—it also scraped all your data, including your likes, posts, and even private messages. Worse, it collected data from all your Facebook friends, whether or not they took the quiz. At best guess, the profiles of 87 million people were harvested.

Zuckerberg on Capitol Hill, April 2018 (Photo by Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Zuckerberg on Capitol Hill, April 2018 (Photo by Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Kogan was a researcher at Cambridge University, as well as St. Petersburg State University, but he shared that data with Cambridge Analytica. The company used the data to create robust psychological profiles of people and target some of them with political ads that were most likely to influence them. Steve Bannon, who was Cambridge Analytica’s vice president, brought this technique and data to the Trump 2016 campaign, which leveraged it to sway swing voters, often on the back of dubious or inflammatory information. A similar tactic was employed by the company in the 2016 “Brexit” referendum.

In 2017, data consultant and Cambridge Analytica employee Christopher Wylie blew the whistle on the company. This set off a chain of events that would land Facebook in the hot seat and Mark Zuckerberg in front of the Senate Commerce and Judiciary Committees.

Giving this the best possible spin, it’s a newer, better version of what President Obama’s campaign did, leveraging clever social-media techniques and new technology to build a smoother, more effective, occasionally underhanded but not outright illegal or immoral political-advertising industry, which everyone would be using soon.

A darker interpretation: It’s “weaponized data,” as the whistleblowers have called it; psyops that use information-warfare techniques borrowed from institutions like the Department of Defense to leverage our information against us, corrupting our democratic process to the point that we can’t even tell if we’re voting for (or against) something because we believe it or because a data-fueled AI knew just what psychological lever to push. Even applied to advertisements, this is scary. Did I buy a particular product because its manufacturer knew just how and when to make me want it? Which decisions that we make are our own?

The irony is that Facebook was sold to its early users as a privacy-forward service.

“You might say ‘Well, what happened before the last election—that was pretty darn malicious,’” says Vasant Dhar, a professor of data science at the NYU Stern Center of Business. “Some people might say, ‘I don’t know—that wasn’t that malicious, there’s nothing wrong with using social media for influence; and besides, there’s no smoking gun, there’s no proof that it actually did anything.’ And that’s a reasonable position too.”

The irony is that Facebook was sold to its early users as a privacy-forward service. You might remember how MySpace faded into oblivion after Facebook arrived. That wasn’t an accident; Facebook intentionally painted itself as an alternative to the wide-open world of MySpace.

Zuckerberg and co-founder Chris Hughes in 2004. (Photo by Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images)

Zuckerberg and co-founder Chris Hughes in 2004. (Photo by Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images)

At this time, “privacy was … a crucial form of competition,” researcher Dina Srinivasan, a Fellow at the Thurman Arnold Project at Yale University, wrote in her Berkeley Business Law Journal paper, “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook.” Since social media was free, and no company had a stranglehold on the market, the promise of privacy was an important differentiation. You needed a .edu email address to sign up for Facebook, and only your friends could see what you were saying. Facebook made this promise initially: “We do not and will not use cookies to collect private information from any user.” In contrast, MySpace had a policy in which anyone could see anyone else’s profile. Users, deciding they favored privacy, decamped en masse.

How Things Went Wonky

(Image: Daniel Chetroni/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: Daniel Chetroni/Shutterstock.com)

Later, as Facebook gathered market share—outlasting, outcompeting, or just buying other services—it tried to roll back some of those privacy promises. In 2007, the company released Beacon, which tracked Facebook users while they visited other sites. And in 2010, it introduced the “Like” button, which enabled the company to track users (whether or not they clicked on the button) on pages where it was installed.

By 2014, after buying Instagram and with a record-setting IPO under its belt, Facebook announced publicly that it would be using code on third-party websites to track and surveil people—thus reneging on the promise it had used to establish market dominance in the first place. In 2017, Facebook paid a $122 million fine in Europe for violating a promise it made not to share WhatsApp data with the rest of the company, which it then did.

In 2019, the FTC announced a $5 billion settlement with Facebook for a variety of privacy violations, including Cambridge Analytica and lying about its facial-recognition software. And in January of this year, Facebook said it would not limit political ads, even false ones. And it won’t fact-check ads or prevent them from targeting particular groups, which is precisely what happened with Cambridge Analytica. Currently, the company is facing intense criticism over its proposed cryptocurrency, Libra.

(Image: vchal/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: vchal/Shutterstock.com)

To scholars like Srinivasan, this is a classic example of a monopoly leveraging its power to make more money at the expense of consumers—not a fiscal expense, since the service is free, but by delivering a worse product; in this case, a product offering less privacy. Market share in social media doesn’t work quite like it does in other industries: The network effect creates a positive feedback loop where, as a site gathers users, it becomes more attractive because of those users, making it particularly hard for a competitor to gain traction. While a company’s size isn’t an indication that it has abused its power, we put up with privacy invasions from Facebook because we don’t have alternatives.

“I want to be a subscriber to a social network, like Facebook, which has more people,” says Nicholas Economides, a professor of economics at the NYU Stern School of Business. “Big size is rewarded. If some company manages to really [gain] big, big market share, like Facebook, or Google in its own area, then it gets big benefits. Consumers really like to be with them. That means they have abilities to control the market.”

At this point, Facebook had so much of the market that third parties such as news sites couldn’t very well uninstall their Like buttons—they needed them to drive traffic.

Big Tech’s Version of Monopolies

Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer in 2000 (DAN LEVINE/AFP via Getty Images)

Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer in 2000 (DAN LEVINE/AFP via Getty Images)

Now that we’re talking about monopolies, it’s time to bring in Microsoft. In 1995, sensing that controlling how people moved across the internet might be even more valuable than the operating systems it already installed on everybody’s computers, Microsoft bundled the Internet Explorer browser into its Windows OS, thus making sure that every computer came with a ready-to-go default browser — Microsoft’s own.

The Department of Justice sued Microsoft, and after a long trial and lots of testimony, a judge ruled that Microsoft be broken up into one part that runs the Windows operating system and another part that does everything else. An appeals court later reduced the penalty, but weakening Microsoft paved the way for a period of technological innovation that gave us Google, Facebook, Amazon, and a renewed Apple. Many economists say that this was the last major antitrust action.

In the 1980s or so, an economic theory known as the Chicago School began to gain favor among lawmakers and judges. It takes a laissez faire approach to antitrust law, limiting the definition of harm to consumers to price increases and claiming the market will sort everything else out. When the price of your social media network, email system, or video hosting is free, it’s near impossible to bring an antitrust suit under this theory. But we need to stop thinking about the users as the customers, according to NYU’s Dhar. “Customers are the people paying them, and users aren’t paying them,” he says. “The users are just supplying them the data that they’re using for the advertising.”

“The tech industry confounds a lot of the antitrust orthodoxy that is applied in the courts and the government enforcement agencies … because competition works differently,” says the EFF’s Stoltz. “Instead of having multiple similar products competing, you have different products, but they compete with one another for access to data, for customer loyalty, and for venture capital.”

In spite of this, states are beginning to take action. A coalition of 50 attorneys general, led by Ken Paxton from Texas, have announced an investigation into Google over its dominance in advertising and how it uses data to maintain that, and others have begun pursuing Facebook over allegations of anti-competitive advertising rates and product quality. The House Judiciary Committee and Antitrust Subcommittee have been hearing arguments about the role of Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple to decide whether the companies have abused their market power. And politicians at the national level, particularly during candidacy, have threatened specific actions, including splitting Instagram from Facebook.

To some degree, this is self-interest, says NYU’s Economides. Facebook’s News Feed and Google News reach a large enough portion of Americans that those platforms can have a big impact on what we see, intentionally or not. Most people probably won’t scroll past their first page of results after a search, so what bubbles to the top (and what doesn’t) is hugely important. “That gives a tremendous amount of power to these companies to shape the political debate … and it’s very hard to take it away,” says Economides.

In 2011, FTC staff concluded that Google had used anticompetitive practices and abused monopoly power.

Google has faced several antitrust investigations. In 2011, FTC staff concluded that Google had used anticompetitive practices and abused monopoly power, including skewing search results to favor its own shopping, travel, and finance sites, and copying content from other sites only to leverage it against them—and threatening to remove them from search if they complained. In 2013, following some concessions by Google but no promises to stop the worst offenses, FTC commissioners voted unanimously to end the investigation. Then in 2019, the FTC fined Google $170 million for tracking the viewing histories of children on YouTube.

Also in 2019, Google partnered with Ascension, a health care operator across 21 states, to obtain lab results, doctor diagnoses, hospitalization records, medications, medical conditions, radiology scans, birth dates and names, addresses, family members, allergies, immunizations, and more from millions of patients without notifying them or their doctors, much less obtaining their consent. This was not a violation of HIPAA (the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), as Google was providing AI software to help suggest better care options for patients. But Google has also sought FTC permission to buy Fitbit, which would give the company even more data on user health, such as sleep schedules, exercise, and heart rate. The Ascension partnership plus the proposed purchase have sparked privacy concerns among lawmakers (the Fitbit deal has not yet been approved).

Fitbit Ionic (Image: Fitbit)

Fitbit Ionic (Image: Fitbit)

Amazon, meanwhile, has captured its market on the back of years of operating at a loss, focusing on growth over profits, predatory pricing, and vertical integration that allows it to exert price pressure on competitors or even leverage its delivery and distribution network against them. Often this has resulted in unfriendly takeovers, like the case of Diapers.com. Amazon tracked prices for diapers on competitor diapers.com, maintained lower prices, and offered promos and discounts in a newly introduced “Amazon Mom” program, only to cut the discounts once Diapers.com’s parent company was forced to sell to Amazon.

“Amazon is exploiting the fact that some of its customers are also its rivals,” concludes Lina Khan, author of a 2017 Yale Law Review article on how Amazon has confounded traditional antitrust understandings.

(Photo by Helen H. Richardson/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

(Photo by Helen H. Richardson/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

The company watches third-party sellers for success stories only to offer similar products under its AmazonBasics brand, at a lower price. Furthermore, the company sets prices variably, depending on several factors, often many times per day. The company has said it does not show different prices to different customers, but the practice makes it hard to prove predatory pricing.

There are consumer benefits to Amazon’s business model. Amazon makes lots of products widely available, and in the case of popular items, very cheap. Its drive for growth over profit has allowed it to woo customers and revolutionize e-commerce. Amazon Prime, for instance, doesn’t exist to make money; its purpose is to get people to shop only on Amazon.

The Value of Data

Data comes into play here, too. Amazon has its own troves, especially related to consumer behavior, which is especially valuable to advertisers. It can trace who has bought what, and when, and from whom (and what you’ve asked Alexa), even things you’ve browsed but not purchased or how long something sat in your cart.

Amazon holds onto data you voluntarily give it, including contacts, images and video you’ve uploaded, special-occasion reminders, playlists, watch lists, wish lists, and more. And the company automatically collects your location, app use, and what websites you visit before and after coming to Amazon.com. In Amazon Go stores and stores that use its Just Walk Out technology, video and deep-learning AI to track who grabs what.

(Image: VDB Photos/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: VDB Photos/Shutterstock.com)

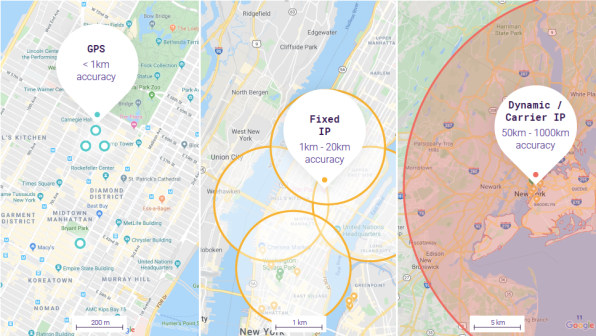

This kind of data collection is not only done by the tech giants. For instance, weather apps track your location even when you’re not using the apps, unless you opt out. That’s ostensibly to provide instantaneous access to weather information wherever you are, but many of them sell your location information to third parties, a practice for which the City of Los Angeles sued The Weather Company.

Some apps are sharing very sensitive information, such as an individual’s sexuality or HIV status. And even though Grindr said it would quit sharing HIV status, Google allows third parties to learn what apps you use—and if advertisers know you use Grindr, they can make a pretty safe guess as to your sexual orientation. If you’ve filled out an OkCupid profile, you’ll remember how it asks you personal questions about your drug use, political party, sexual proclivities, and what side of the bed you like to sleep on. This info is used to help select matches for you, but the company is also sending that information to an adtech company called Braze.

Earlier this year, the FCC fined major cell phone providers $200 million for selling consumers’ real-time location data to third parties. The New York Times obtained one file of such data, which it used to discover cell phone users’ addresses and places of work, including public officials and political protesters. “They can see the places you go every moment of the day, whom you meet with or spend the night with, where you pray, whether you visit a methadone clinic, a psychiatrist’s office or a massage parlor,” the Times reported.

The Business of Selling Data

So who’s buying that information? It’s not advertisers, at least not at first. A shadowy network of hundreds (or maybe thousands) of third parties known as “data brokers” (or sometimes the “adtech” industry, though the two are not precisely interchangeable), collect and process data from many distinct sources, including credit reporting, ID verification, public records, smartphone data, browser history, loyalty programs, social media, credit card transactions, connected devices, information scraped from websites, market research, and so on. Some of it is publicly available, and some of it is purchased.

These are companies you probably haven’t heard of. They use a unique identification number to collate huge parcels of information on us. They’ve built a virtual profile of you not unlike what Cambridge Analytica did. So you’re influenced by factors you’re unaware of but that the data brokers know all about: They know which buttons to push or levers to pull and when to get you to do what they want.

Those ads that make it seem like your phone is listening, but perhaps they’re so good at understanding you that they are actually predicting what you’ll be talking about. This isn’t as far out as it sounds. If their profile of you is inclusive of your interests, an AI with sufficient data can likely infer many of your topics of conversation.

It’s not just about selling you things; it’s also about persuading you to do things, which happens to be buying what an advertiser wants you to buy.

Remember, this all rides on big data. It’s not that at one time you bought this thing and you posted your mood about it and therefore they think maybe you’ll be interested in this other thing. It’s aggregating all the places you’ve gone and all the things you’ve bought to make predictions of your consumer behavior. Then that gets sold to advertisers. It’s not just about selling you things; it’s also about persuading you to do things, which happens to be buying what an advertiser wants you to buy.

Your data is often sold to advertisers, but data brokers can also sell to other parties, including credit scoring and insurance companies. And because two individuals won’t see the same ads, it’s difficult to spot price discrimination, disinformation, and other exclusions. The brokers put together lists that potential advertisers might be interested in, such as homeowners, runners, or video gamers—but sometimes it can get much darker, as in 2013, when data broker MEDbase 200 was caught offering lists of rape victims, alcoholics, and sufferers of erectile dysfunction. And in 2017, Facebook allowed housing advertisers to ensure that ads for housing were not shown to African Americans, and boasted to other advertisers the ability to target teens who felt insecure, worthless, anxious, useless, and more.

Once an entity has bought your data, there’s a bidding war. From the time you click on a page to when the ads load on that page, potential advertisers use automated tools to bid on how much they are willing to pay for you to see an ad, and the results of that real-time bidding are then added to your profile.

Amazon, for example, does not sell the data it collects (which you can see and control here). But it does allow third parties that serve ads to install cookies, which they can use to gain information about you, including your IP address and more. And Amazon does buy data from data brokers, in what’s called “pseudonymized” form—your name is replaced with a different identifier, like a random number—which can then be paired with your profile to target ads. As the Times found, it’s easy for parties that have some portion of your data to match it to other bits, to create those robust, predictive profiles.

What Are Lawmakers Doing About This?

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Several recent major pieces of legislation have tackled the privacy problem, and more are forthcoming. The EU, in 2018, implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which applies standards for keeping data secure, a legal liability if companies fail, and required practices if a hack should occur. It also gives citizens the right to access their personal data and to ask the companies holding it to delete it.

In 2020, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) took effect, which is similar in some ways to the GDPR, allowing internet users to request the data that has been collected on them (and learn where it was sold), to request that it be deleted, and to opt out of future collection. Facebook, Google, and many others revamped their privacy pages, allowing users to toggle what the companies could and could not collect, and what they could and could not do with what they collected. The law applies to data brokers too, but you have to contact each one yourself, assuming you can find them. So a startup called DoNotPay has begun offering an automated service that contacts data brokers on your behalf and demands that they delete your info.

In the absence of a national policy, other states are building their own legislation. A number of states, from Florida to Washington state, considered consumer privacy bills this year, but few gained any real traction, in part due to COVID-19 restrictions. In Congress, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) has proposed the Data Protection Act, which would create an independent federal agency to oversee data privacy and security.

Privacy groups and tech companies have pointed out flaws in some of these regulations, including loopholes (companies may reject user requests for data, for example, saying they require identity confirmation). Remember that real-time bidding war you set off when you click on a link with ads? If you decline to allow companies to sell your data, as CCPA allows Californians to do, that bidding happens without the bidders knowing as much about you, and the ad is less valuable. But Google has found a way to turn this to its advantage: When a user opts out, Google does not allow other parties to bid at all, restricting it to its own, in-house bidders.

(Image: Trismegist san/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: Trismegist san/Shutterstock.com)

And these laws are new enough that it’s unclear how effectively they’ll be enforced, and to what extent. Legislation can have unintended consequences, points out Ashutosh Bhagwat, a constitutional law professor at the University of California–Davis. Any policy that undermines the basic business model of an industry needs to offer an alternative unless we intend to live without social media altogether. (Not likely.) And paying for services rather than relying on advertising can accentuate the “digital divide,” denying social media to people around the world who can’t afford it.

“I think the privacy concerns are somewhat legitimate, but I think they’re a little overblown. There’s a lot of, ‘the sky is falling’ kind of stuff going on, and I don’t think we’ve quite got to that point yet. Maybe facial recognition will be the technology that’s the killer app for privacy,” says Bhagwat. “People vastly exaggerate how easy it would be to solve this [privacy] problem.”

Although the current COVID-19 pandemic has dominated the media cycle, some of these issues are coming to a head behind the scenes as people work from home and spend more time online. Online meeting software Zoom was busted, and then sued, for sending information—including device, operating software, carrier, time zone, IP address, and more—to Facebook without permission via the “Login with Facebook” SDK. (Zoom has since removed the SDK.)

Although the current COVID-19 pandemic has dominated the media cycle, some of these issues are coming to a head behind the scenes

Meanwhile, governments around the world have been using a variety of phone data to track and combat the disease, including enforcing social distancing and mapping the spread. Many have raised concerns about sacrificing privacy during a crisis, only to never get it back, but the response in Taiwan, where the government installed location trackers on the phones of people suspected of having COVID, has been positive because policies there have been so effective at stopping the spread. Kinsa Health has been cheered for its ability to quickly spot potential outbreaks—sometimes weeks ahead of the CDC—based on the body temperatures of its users sent to the company by its smart thermometers.

Google has launched a site that offers community mobility reports, which uses location information to show public health officials (or anyone who wants to look) where people are and aren’t going. Google says the information is collected in aggregate and won’t show actual numbers, just percent change. Through it all, Congress has been moving forward with the EARN IT Act, which would eliminate end-to-end encryption (as used in messaging apps like WhatsApp or Signal) in the name of fighting child exploitation.

Still, some sort of privacy regulation is necessary, says the EFF’s Stoltz. “Broadly, they take the right approach to privacy, in that they start from a framework of privacy being a human right, not something that a person can sell or trade away,” he says. “We really do need both baseline privacy rules … [and] robust antitrust law that says the concentration of economic power is harmful, just like concentrations of political power are harmful.”

Feature Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

By Nathan Hurst

Sourced from PC

(Image: Ink Drop/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: Ink Drop/Shutterstock.com) Zuckerberg on Capitol Hill, April 2018 (Photo by Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Zuckerberg on Capitol Hill, April 2018 (Photo by Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images) Zuckerberg and co-founder Chris Hughes in 2004. (Photo by Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images)

Zuckerberg and co-founder Chris Hughes in 2004. (Photo by Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images) (Image: Daniel Chetroni/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: Daniel Chetroni/Shutterstock.com) (Image: vchal/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: vchal/Shutterstock.com) Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer in 2000 (DAN LEVINE/AFP via Getty Images)

Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer in 2000 (DAN LEVINE/AFP via Getty Images) Fitbit Ionic (Image: Fitbit)

Fitbit Ionic (Image: Fitbit) (Photo by Helen H. Richardson/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

(Photo by Helen H. Richardson/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images) (Image: VDB Photos/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: VDB Photos/Shutterstock.com) Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images)

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images) (Image: Trismegist san/Shutterstock.com)

(Image: Trismegist san/Shutterstock.com)