By Cillian Bracken Conway

If used correctly, Google AdWords can be an extremely profitable online advertising channel for your business. However, PPC advertising on the Google platform is quite technical; specialised knowledge and experience are required to generate consistent ROI.

You likely don’t have the time to learn nor run a Google advertising strategy. This is where a Google Ads agency comes into play.

Like any agency, a Google Ads agency will save you time and effort and potentially make you money. Outsourcing is crucial for any business; you can’t do everything yourself.

Finding the right agency for your organisation will require careful consideration. Below, we’ve listed six major red flags you must watch for when choosing a Google Ads agency.

-

They “rent” the account to you because the bid strategies are their IP.

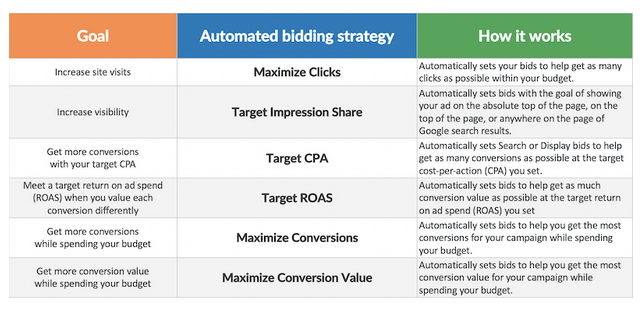

There are agencies out there that insist on ownership over bid strategies. When looking for a Google Ads agency, this is a scenario you’d want to avoid. Bid strategies shouldn’t be considered proprietary; look for an agency that’s transparent with your organisation.

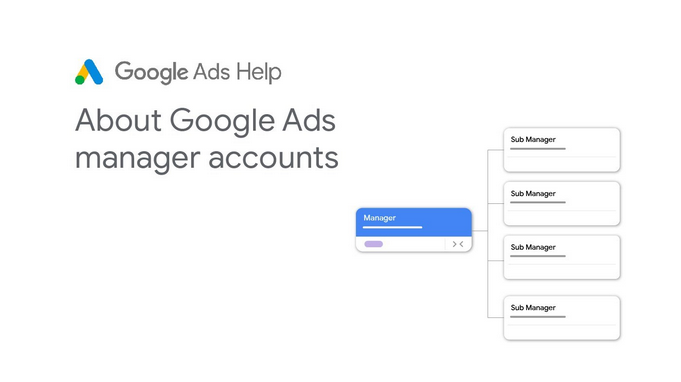

2. They don’t provide you with full access or ownership of the account, or worse, they say that they “own” it.

You must have full access and ownership to your Google AdWords account. Agencies have an ethical obligation to give clients complete control. Some don’t, using it as a way to lock clients into their contracts.

Having full access to a Google AdWords account is essential for several reasons. Firstly, you’re able to see if the reported figures the agency gives you is accurate. Secondly, you can remove their access if you decide to terminate the contract.

It’s also important to mention that Google AdWords accounts with longer tenure are preferred. Your account history influences your performance and, ultimately, the ROI you generate from paid search.

Because an existing account has more data than a new one, Google rewards better quality scores. All that data is also a guide for what hasn’t worked; you’ll be less likely to make the same mistakes.

It’s preferable to maintain control of a Google AdWords account because you don’t want to create new ones. You don’t have the time and effort to continually build a new account every time you change PPC agencies.

Be cautious when signing a contract with an agency; there could be terms and conditions regarding ownership. If you don’t have a Google AdWords account and the agency wants to make you one, ensure it’s done through their Google Ads manager account.

3. They won’t provide a detailed breakdown of how they optimised the account in a given time frame.

One of the most significant red flags to look out for regarding PPC agencies is if things are too stagnant. Successful, well-managed agencies will regularly implement changes and tweaks to optimise ad campaigns.

This could be several things, for example.

- Bid changes

- New or refreshed ad copy

- Bid adjustments

If an agency tends to run things on autopilot, they’re likely not utilising the ad spend effectively. More specifically, keyword bidding is probably done automatically, which leads to overbidding, resulting in wasted budget and inactive ads.

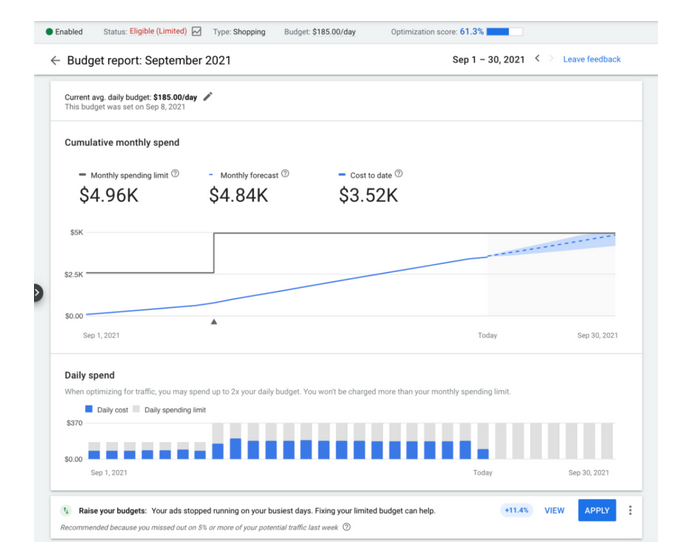

4. They won’t provide a detailed breakdown of where your money was spent.

It’s concerning if an agency doesn’t provide a frequent report that tells you how your ad budget is being spent. Many businesses take a hands-off approach when it comes to their Google advertising strategy. They outsource the work to an agency and assume everything is good.

What these organisations don’t realise is that agencies often charge high management fees. It can be as high as 30-40% in some cases. This means less of the ad budget is being used for ads.

To avoid this, agencies should be able to present, at any moment, a budget breakdown to a client. It should become a frequent habit, one that’s expected every week, fortnight, or month. Transparency is the focus here.

5. They don’t focus on important metrics like, you know, conversions and return on investment.

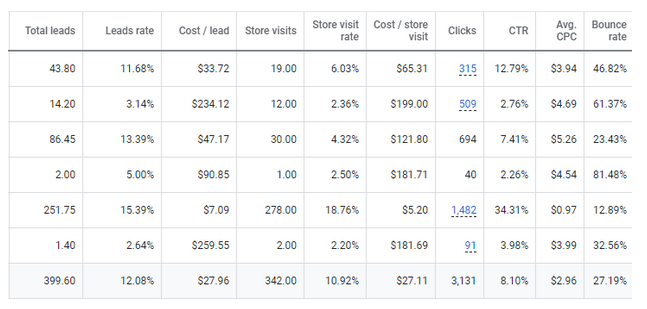

You can only know if your Google Ads benefit your organisation by looking at the data. Metrics like conversions, clicks and return on investment give us insight into the effectiveness of campaigns on the Google Ads platform.

A Google ads agency should provide data-rich reports that detail whether or not ads are profitable. Unfortunately, some don’t; this is a major red flag. Consider bringing up the topic of metrics when you’re interviewing potential candidates.

A Google Analytics account that you can access should be linked to your Google AdWords account. Conversion tracking and event snippets are also a must.

6. They never asked for detailed information on your business, your USP and your industry.

An ad performing well and providing a positive Return on Ad Spend is dependent on more than just the amount that you bid. The context, relevance, and a solid quality score can determine how much you pay for that click. Even the performance of your post-click landing page affects your ad and the cost.

The agency that you hire must understand your business and its unique selling proposition. They must also have verifiable experience within your industry; Google ads is particular and contextual. What works for one field isn’t going to work for another.

When screening and interviewing potential candidates, question them on their industry knowledge. Ask if they have any tangible examples of success with prior clients similar to your organisation.

Conclusion

An effective Google ads strategy is one of the best ways to increase the revenue of your business. It is, unfortunately, something that requires time, effort, and expertise — things that you may not have right now.

A Google ads agency is a fantastic solution to these concerns.

In this article, we outlined six different red flags that you must consider when choosing an agency. Hopefully, the information detailed provides some value to you and your organisation.

Are you looking for an agency that can help you grow your business with Google AdWords? Please contact our PPC advertising team today to learn how Vine Digital can help you get more from your advertising spend.

Glossary

Pay-Per-Click (PPC)

Pay-per-click (PPC) is an advertising model where advertisers pay a publisher every time their ad is clicked. A publisher could be a search engine, like Google, a website owner, or a network of websites. The publisher hosts the advertiser’s ad to an audience.

Unique Selling Proposition (USP)

A unique selling proposition (USP) is a marketing strategy that informs potential customers how a brand’s product or service is superior to competitors. USPs are used as a tactic to differentiate a brand from the rest of the marketplace.

Conversion

A conversion is a desired action taken by an individual who has seen an ad or marketing material. It’s a nonspecific umbrella term for any intended goal that a business is hoping to achieve. Conversions can be measured and tracked with analytics and reporting features.

This could be signing up for an email list via a landing page or purchasing a product or service. Other examples include clicking on an ad, visiting a webpage, or watching a video.

Return on Investment (ROI)

Return on investment (ROI) is a financial metric that evaluates the efficiency of an asset, such as an advertising budget. It determines whether something is profitable for a business.

Bid

A bid is the amount of money you’ve committed to an auction for a specific ad space opportunity. In the context of Google ads, every keyword/search term provides an opportunity for you to advertise your business.

Bid Strategy

A bid strategy is a uniquely tailored campaign offered via the Google AdWords platform. Each of these campaigns has a specific goal in mind, such as clicks, impressions, conversions, or views. Businesses will choose the bid strategy that best aligns with their current ad goals.

Negative Keyword

A negative keyword is a keyword that stops your ad from being activated by a specific word or phrase. Negative keywords prevent your ads from being shown to users searching for that particular phrase.

Conversion Tags

Conversion Tags are snippets of code that help with conversion tracking on a website.

By Cillian Bracken Conway

Cillian Bracken Conway is Managing Director at Vine Digital with 15 years of experience working in SEO & PPC. https://www.vinedigital.ie/